Berkeleyan

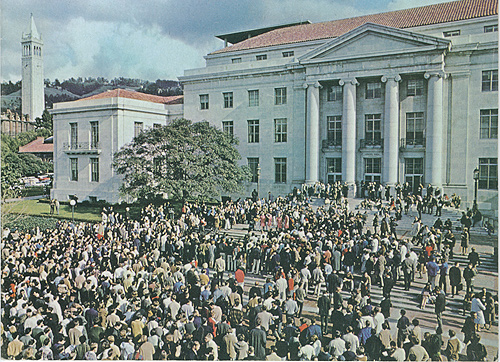

Sproul Plaza filled with Berkeley students, circa 1967, from a brochure published by Campus Crusade for Christ. (Source: Public Affairs) |

Where Were You in ‘68?

Faculty and staff memories conjure a tumultuous decade’s most eventful year

![]()

04 June 2008

WHAT I REMEMBER MOST about 1968 is that it is the year my sixth-grade teacher changed my life, opening my mind to the world and its possibilities. He introduced me to The Little Prince, Shakespeare, and Langston Hughes, and algebra and the scientific method. He taught me to embrace challenges, not fear them. He taught me to honor where you come from, but that what matters most is where you’re going. I was a young black girl, the child of recent immigrants, and empowerment was not in my vocabulary, but Mr. Litwalk empowered and inspired me in ways I’ll never forget. When I reflect on 1968, it’s the hours spent in his classroom that I remember most vividly.

Andrea Green Rush, executive director, Berkeley Division of the Academic Senate

I GRADUATED FROM CAL in 1968. One of my most vivid memories is of the day that Martin Luther King was killed and the day or two afterward. At the time I was very involved in the Stiles Hall Student West Oakland Project, heading up a tutoring program at a middle school in West Oakland and serving on the project’s Steering Committee. The evening that King was assassinated, we had a steering-committee meeting scheduled and had planned a birthday celebration for Stiles Hall's director; instead we gathered and mourned.

Later — I think it was the next evening — some of us were called to a meeting at a vice chancellor’s house to advise on how the campus should acknowledge the event. It was decided that classes would be cancelled for the afternoon of the next day so that students could go to religious services nearby; that there would be a special carillon concert of spirituals played at the Campanile, followed by “We Shall Overcome”; and that students would gather at Sproul Plaza for a minute of silence and could then voice their feelings.

I sat on the Sproul Hall steps that day, listened to the music, and cried, while thousands of students gathered. After the music and the silence, someone stood up and said some words honoring King, but then another student stood and said that King had sold out to the White establishment. Before long, there was an active, heated debate — shouting and pointed fingers. I remember thinking, “A young man — a father, a husband, a great leader — is dead. Can’t we just honor him for a moment and fight this out later?” It was the beginning of a depression, personal and national, that set in and grew over the rest of the year, with Bobby Kennedy’s assassination, the Democratic convention in Chicago, and the deepening Viet Nam war. 1968 was not a good year.

Irene Hegarty, director, Community Relations

IN 1968 I WAS a student at what was then Humboldt State College. Robert Kennedy was barnstorming through the state immediately before the June 5 primary, and I went to the McKinleyville airport with my roommates to see him arrive. The North Coast was a mellow place in those days, seemingly far removed from the rest of the world, but when Bobby came to that little airport and walked down the fence greeting us, we felt electrified and connected to the larger world.

Jim Horner, campus landscape architect

IN THE LATE AFTERNOON of a remarkably clear October day in 1968, I was asked to address the full Academic Senate (in those years, Senate meetings could draw as many as 600 faculty — and Wheeler Auditorium was overflowing that day), to defend a new course that had been officially approved, but which had raised the ire of then-Governor Ronald Reagan. As governor and a member of the Board of Regents, Reagan had promised to “stop the course” from being taught. This was a transparent violation of faculty authority — a blatant political intrusion into the arena of faculty governance at the core of the idea of institutional autonomy. How did this happen?

In the early fall of that year, a committee of the Academic Senate with authority over what was then au courant Experimental Education would consider and approve a number of “Student Initiated Courses.” Undergraduate students could propose a course framework and some content, and if they could get some faculty member(s) to sign on as official instructor(s), the course would usually be certified for academic credit. It was obviously not a common procedure, but perhaps a half dozen such courses were approved each year.

The Black Panthers of Oakland were very much a part of a new kind of political consciousness that had captured and animated scores of progressive students. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated the previous spring, and Black Studies courses were being demanded across the country — most notably and notoriously, just across the Bay at San Francisco State. Huey Newton was still in prison, and Eldridge Cleaver was one of their two most visible spokesmen, author of a recently published best-seller, Soul on Ice. (The other was Bobby Seale.)

That is the context in which several students came to see me and Jan Dizard, a young assistant professor of sociology — to ask if we would co-sponsor a new course, 139X (X was short for “experimental”). The course would feature a series of lectures by Eldridge Cleaver and would have a reading list approved by the instructors. We agreed, and then two other instructors from the psychology department were added as co-sponsors.

When the local news media picked up the story that Eldridge Cleaver would be lecturing at Berkeley, a right-wing political firestorm erupted. Reagan, who had won his election in some measure by running “against Berkeley and its unruly students” — and who had fired UC President Clark Kerr for his resistance to raising student fees — immediately saw political opportunity and vowed to not permit the course. We four instructors were asked by some of our colleagues to withdraw sponsorship, to avoid the kind of confrontation that had cost Kerr his job — but many others urged us to stand firm. We did not really need cajoling: Each of us had already pledged not to budge an inch.

So, with the exception of the assassination of King, my most memorable moment of 1968 was my address to the Senate — and witnessing the subsequent near-unanimous vote to continue with the course, “on campus, for credit.”

Troy Duster, Chancellor’s Professor, sociology

MY MEMORIES OF 1968 are still vivid, but I have for long preferred not to dwell much upon them.

That fall quarter, like every semester and quarter since fall 1964, involved undertaking tasks that impeded my scholarly work (though never my teaching). Then, as before and after, I undertook much responsibility for the Department of History's physical security, as the departmental space officer. I also helped to protect professors whose classes were threatened by disruption — particularly Martin Malia's large lecture class on the Soviet Union — by close coordination with the University Police. At one point, by a classical stratagem of the outnumbered, I helped a single UCPD officer turn back a mob attempting to disrupt the Chancellor's Office, which is where the history department's meeting room is now.

I lived through it all, I was involved in it all, and in the eyes of the faculty and student left's Zeitgeist, I was on the wrong side. I lost my liberal naivete as an Assistant Dean of Students in the “Free Speech” fall of 1964. I witnessed the arrest of Jack Weinberg, the riotous attempt to rescue him, the interference with the police in execution of their duty, the destruction of property. I believed then, and believe now, that the rule of law is essential to the civil polity and good order essential to the academy, and there was too much simple lawlessness and disorder, dressed in idealism and youthful spirits, afoot in the 1960s. I also believed the Vietnam war was just and in the nation's interest, and that clearly put me beyond the pale by 1968. And I suppose that is where I am now, and must remain!

Tom Barnes, Professor of history & law; Co-chair, Canadian Studies Program

I ARRIVED IN CHICAGO about a week after the Democratic convention. Twice before I even reached Hyde Park and the University of Chicago, where I was going to start my Ph.D, I was pulled over by a cop in a squad car. And it happened three or four more times over the next week as I scurried about for student furnishings.

It was a simple problem: I was naively driving a pickup truck with a camper shell, Oregon license plates, and a Eugene McCarthy sticker on the bumper, and wearing the same beard I wear today . . . albeit then dark brown. Although I was coming into town to become a Chicagoan for a couple of years, the only thing the cops saw was a McCarthy-loving Oregon hippie who hadn't been driven out yet.

Richard Norgaard, professor of Energy and Resources

I WAS A SOPHOMORE at Cal in 1968, living in Griffiths Hall. I was elected President of the Hall, and had the opportunity to meet Ruth Donnelly, then Director of Housing, who had been a student at Cal in the 1920's. I remember the first time I met her, in the temporary housing office that remained at Bowditch and Channing until the construction of the Crossroads dining facility. She used a cane, and wore bright lipstick ... she seemed so old to me then, and steeped in values from a different time.

As with many of the changes overtaking the campus and the nation, 1968 was also the year that “lock-out” ended in the women's dormitories: Women were no longer punished for returning to the residence halls after a prescribed hour. It was also the year men were allowed “visitation,” which meant a woman could visit a man's dorm room as long as the doors were kept open at least one yard. Modernity had reluctantly reached even the campus housing office; 1968 was that kind of year.

That summer I continued to work at home as a member of the Retail Clerk's Union, bagging grocieries — the job I had as a senior in high school. I earned excellent wages: $1.67 per hour, $2.15 on Sundays and holidays. My Alumni Association Leadership Scholarship was not renewed for my sophomore year, so I needed to make up the $300 that it provided, which allowed me to pay the $77.50 per quarter that were my fees my freshman year. The fees went up in 1968, and it was a harbinger of things to come regarding access for those like myself whose families had limited incomes. But with my State Guaranteed and later Federal loans, I was able to pay the $1,000+ per year costs for housing, and the $40 a month my parents were able to send me took care of my personal expenses.

As the only student from my high school to come to Cal my freshman year, I met a whole new world of friends some of whom remain close to me today. We would go to dances in the Rec Room of Unit II to listen to a local band, Frosted Suede, and talk politics, Cal football, and life late into the night. Yet the winds of change were blowing hard. Between anti-war demonstrations outside the classroom, the Third World College Strike, national politics, the tumultuous end of the traditional ASUC at Cal, and my own personal growth and emergence from childhood, it felt like a cathartic year. I had to balance the values of my parents, as straight-arrow immigrants to the U.S., with my experience of a setting that was challenging every traditional value and attitude that I possessed.

The assassinations of Robert Kennedy and the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the awful 1968 convention in Chicago were the backdrop to these exciting, complex, and intense times at Cal. The confluence of events outside of the small world that Berkeley in fact was were reified by a real world that tested what we learned in the classroom. These lessons helped to transform me, to broaden and deepen the way I looked at issues and events.

I've been at Cal for 41 years, and even today as I walk through Sproul Plaza to administrative meetings or to teach my classes, I can still recall how sweet it was to be a Cal student and to have experienced Cal as a student. As student, graduate student, employee, manager, faculty, and alum, I have had the good fortune to be here and to savor this place. I have learned to balance the traditional with the progressive, the conservative with an unabashed commitment to change, and Cal with Berkeley. 1968 was the year this balance began to take shape and become a fundamental part of who I am.

Nadesan Permaul, director, ASUC Auxiliary; lecturer, rhetoric and political science

IN JUNE OF 1968 I graduated from a nice, middle-class high school in west Los Angeles. And not a minute too soon. I was primed for tackling Big and Significant things. I wanted to join The Revolution: Any revolution would do, as long as it wasn’t in L.A. What I really wanted to do, though, was go to school in Berkeley.

I had heard about this mysterious and dangerously politicized Oz four years earlier. The brother of a neighbor of my cousin used to send regular, thrilling dispatches from the front, letters that regaled us with his adventures with something called the Free Speech Movement. The letters would inevitably also include posters, manifestos, and, best of all, little badges printed with slogans and organization names, which we could pin to our shabby corduroy jackets to confound and disturb the bourgeoisie (our parents, in particular).

Although I wanted to trek north so badly my teeth hurt, my parents couldn’t manage sending me away to college, and I was basically too lazy to work for the privilege, and probably too fundamentally timorous to make the leap. UCLA is where I ended up for my four undergrad years. My best friend Fred, however, was luckier (or smarter and more ambitious): He headed north to school with a duffel bag full of Levis and chambray workshirts, a stack of Cream and Dead records, and most likely a sizeable stash of contraband herbage. What more did one need at 18? I was, of course, massively jealous, and I jumped at his invitation to come up for a visit in late fall of that year.

Fred picked me up from the Oakland airport on his little black Honda motorcycle, and we immediately headed straight for Telegraph Avenue. I remember having dinner at the Top Dog on Durant and dessert at the Swenson’s ice cream shop next door. We checked out Leopold’s Records, Moe’s, Shakespeare and Co., and the Print Mint. We strolled down Telegraph, a scene as strange and slightly scary to me as a Hieronymus Bosch tableau.

The next day we toured campus, which involved a broken-field walk through a large and obstreperous rally of some kind in Sproul Plaza. I wasn’t really listening; I was participating in my own personal brand of liberation politics, and the rhetoric didn’t really matter. I distinctly remember being deposited by my friend later that day in the unbelievably cozy Morrison Library to listen to music and simply soak up the elegance. For years afterwards I thought that Morrison was the Berkeley Library. If I ever became a librarian (and the thought had crossed my mind in high school), that’s where I wanted to work.

And here I am — here I’ve been … for close to 30 years now, on the same campus that so notably thrilled and inspired my 18-year-old self. And there probably isn’t a week that doesn’t go by that I don’t think fondly for how amazing that first Top Dog tasted 40 years ago.

Gary Handman, The Library, Teaching/Media Resources

"I DON'T REALLY KNOW what I think until I try to write it down.” One of my favorite English professors said that in class and I’ve never forgotten it. I’ve also never tried to write about my experience of 1968. The news headlines were devastating: Vietnam, Martin Luther King, Bobby Kennedy, the Nixon-Humphrey presidential race. The prospect of graduation from a small liberal-arts men’s college in New England was traumatizing enough without the intervention of the outside world. It was like running stark naked off the end of the high board over an empty pool. The big question was: What next?

The pressure was intense, internally and externally. There was reading to finish, papers to write, and days of comprehensive exams to take. The outside world seemed to have lost its mind; violence was everywhere. From our bucolic setting in western Massachusetts we “benefited” from the TV news with images of blood, body parts, and carpet bombing. From the Berkshires we sought news of Berkeley, where the resistance movement was centered. America’s cities were ablaze. Draft deferments were withdrawn. And exams loomed. Then — oh God! — graduation. Many seniors in our house gathered late in the evening over cold coffee, planning the shortest route to Canada, but none of our personal plans could withstand the next news broadcast. Shortly we would don the robes, walk the walk, and turn in our dorm keys. Somebody spoke; I tried to translate the Latin on my diploma as I pretended to listen. Now what?

I returned to Southern California and total uncertainty. My moustache drew hostile glares in middle America and I found my home state completely fractured. The college cocoon was long gone and I felt alone in a violent country; threats everywhere. My friends were dispersed, my family didn’t understand my angst, and President Johnson wanted to send me into a jungle war that I despised. For the most part, the second half of ’68 is a blur in my memory: no recollection of work, friends, lovers, Christmas, the World Series. There was only war, politics, and the draft. Then came the morning when I was getting ready for work and collapsed on the kitchen floor. The doctor said it was a stomach ulcer, and suddenly the clouds parted: I was 4F, and my life could begin again.

They say that worry never solves anything. This time, they were wrong, but I’ve had 40 years of pain.

Anthony Bliss, curator, Rare Books and Literary Manuscripts, The Bancroft Library

I WAS A FRESHMAN here at Berkeley in the fall of 1964.. I was very affected by the Free Speech Movement and the civil-rights marches in 1964-66, then was out of the country for the 66-67 school year. It was quite amazing to read about the Haight-Ashbury from halfway around the world; I grew up one neighborhood away from there in San Francisco. I returned to Berkeley to finish school, but the escalation of the Vietnam war, the assassinations of King and Kennedy, and the election of Nixon (and the miserable lead-up to it) grabbed a lot of my attention in 1968. I would have to have been pretty much comatose if they hadn't.

My husband (then my boyfriend) and brother had major draft worries, and it seemed that we and everyone we knew went to demonstration after demonstration against the war. It took me years to be able to talk or think about the draft without having my stomach knot up. Those were the days — but then, these are too.

Erica Roberts, department of comparative literature

I WAS 11 YEARS old, growing up in Oswego, N.Y. My most vivid recollection was that I idolized my big brother, who had a big, red peace sign on his dresser and his own stereo where I came to listen to Simon and Garfunkel, James Taylor, and, in the coming years, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and Cat Stevens.

The other events that stand out in my mind were the two back-to-back assassinations —Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy. I was especially saddened and felt a sense of hopelessness when Bobby Kennedy was killed. 1968 was the beginning of my love of music and understanding of the world outside myself.

Nadine Marturano, College of Letters and Science Computing Resources

IN 1968, AT THE age of 41, I was in Berkeley, having been employed in the Department of History since the previous year. By the estimate of importance that I made then and make now, the major events of 1968 happened in Prague. The people of Czechoslovakia rose in revolt against the totalitarian rule of the Communists and were suppressed by Soviet forces.

Raphael Sealey, professor of history

IN 1968 I WAS a 22-year old secretary at Cape Canaveral, working for the engineers responsible for all the photography (still and motion-picture) during the Apollo moon launch program. I was supposed to type perfect letters with seven carbon copies (I often failed). On my 21st birthday, my boss got a top-secret-clearance badge for me (I only had “secret” clearance) and spirited me to the top of launch tower 39. Later that day I was taken to a concrete bunker and got to push the button that launched a weather rocket into space.

I was oblivious to the Vietnam war, unaware of much of the civil-rights unrest. Then, on a short vacation visit to San Francisco — where I was shocked (shocked!!!) to have been offered a marijuana “cigarette" — my education of the world beyond the occasional alligator blocking the roadway to Kennedy Space Center began. Three years later I moved to Berkeley.

Rita Gardner, executive assistant, Vice Chancellor – Administration

I WAS 26, AND had finished my master's degree in paleontology/geology at the University of Oregon. My husband and I were left-wing. I had long hair and didn't wear a bra. We tried not to get too depressed by what was happening in Vietnam and the assassinations of King and Kennedy. The Beatles made things better. We backpacked on the Olympic Peninsula beaches, ate lots of steamed mussels, drank Gallo Hearty Burgundy, and slept in our VW bus. Gas was 29.9 cents a gallon.

Carole Hickman, professor of integrative biology

1968 IS A VIVID year for me. I was 13, and that summer my family moved from England to the U.S. Our first month, August, was spent in the ramshackle buildings of an old Girl Scout camp on an island in the St. Lawrence River. There was one crackly TV on which I watched, fascinated and perplexed, the Republican convention at which Nixon was nominated. I'd never seen anything even remotely like it in England, of course: The convention proceedings, with the corny theatrics (The Great State of Vermont Declares for Richard Nixon! ) hats, streamers and the like seemed very undignified and not the way that the serious business of government should be conducted. Later that summer, the Democratic convention was even more startling, for the demonstrations and violence in the streets standing in such extraordinary contrast to (what looked to me like) the ebullience in the convention hall.

Also memorable was the good-looking older son of the family we were staying with, who hung out in the boathouse smoking weed and listening to Bob Dylan.

Jane Mauldon, associate professor of public policy

I SPENT PART OF 1966 as a consultant in Ronald Reagan's campaign for governor; among the reasons for his success had been his denunciations of campus protests. I moved to California in 1968 and began teaching at Cal that fall. At my first class, I was surprised to find only a dozen undergraduates in the room; I was told to expect 30. Half an hour into the session, additional students started sauntering in and confiding to all who'd listen that they had triumphantly occupied Dean Knight's office in Moses Hall. The troops of occupation had been led by anti-war activist Tom Hayden, who had hastily abandoned them the moment the police arrived, making his ignominious retreat out a back window. The students were atwitter; I was disquieted but curious to find what further surprises lay ahead. (P.S., I have since come to love the energy and real love of learning of Cal undergrads.)

William K. “Sandy” Muir, professor of political science

I DIDN'T MEAN TO keep hitting Ronald Reagan on the head with my tape-recorder microphone, but I was wedged right up against him by the UC cop escorting him through a raucous and unfriendly crowd of students. Reagan was walking along, trying to speak with a student on his left side, while I, on his right, kept trying to stick my mic in front of his mouth. Reach/clunk/oops, reach/clunk/oops ... nearly all the way to his limo.

It was the end of the second day of a tense UC Regents meeting at Santa Cruz. The top item on the agenda was the controversy over Social Analysis 139X, an experimental course on race issues developed by Berkeley students under faculty supervision. (See Troy Duster’s memory of 1968, above, for more on the genesis of 139X.) The primary lecturer was to be Eldridge Cleaver, the Black Panther leader and author of Soul on Ice; his scheduled participation, anathema to the conservative majority on the board, led them at first to withhold credit for the course. (In typical regental fashion, the ban was couched in the most general language, providing only that credit be withheld from any course in which a guest lecturer appeared more than once.) That action was roundly condemned by Berkeley’s Academic Senate, supported by then-Chancellor Roger Heyns, even as pressure on the campus to bar Cleaver altogether was being exacted by the likes of Reagan and the state of California’s nutjob public-education honcho, Max Rafferty. Demonstrations and building occupations on the Berkeley campus led to the arrest of some 200 students.

We were following the controversy at UCLA, where I had just started my freshman year. As a would-be journalist getting involved with the campus radio station and student paper, I volunteered to travel to UCSC for the climactic Regents meeting, at which the question of credit for 139X would (it was thought) be finally resolved. Though ensconced in a Westwood dorm, I had friends in Berkeley and Santa Cruz, and this seemed like a dandy way to spend some time with them while advancing my journalistic bona fides.

Over the course of two days, I learned more about what it takes to be a good reporter than I’d absorbed in five years of secondary-school journalism. In addition to sitting in on the Regents meetings — when longhaired me could wangle access to the meeting room, that is — I roamed the campus, interviewing students, faculty, and anyone else who looked agitated and willing to talk, phoning in reports to KLA-AM and the Daily Bruin as events warranted. It was something new and exciting to me to keep on top of a fluid and complex situation, competing for access to principals and players with veteran beat reporters from the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, and numerous radio and TV stations. It was exhilarating and exhausting . . . and, finally, it was over, with no permanent resolution of the 139X crisis having been achieved after all.

Reagan had, during the second day of meetings, introduced a radical resolution that would have gutted the principles and practice of shared governance at UC, relieving faculty of the authority to (among other things) authorize courses, make faculty appointments, or participate in university governance. The Regents voted him down on procedural grounds. After the board adjourned, he met with angry students for half an hour, then started to walk to his limo — which is when I, microphone in hand, got wedged up against him by the crowd that shadowed him nearly all the way. Emboldened by my new sense of journalistic mission, I followed him the rest of the distance, calling out as his driver opened the back door. “Mr. Reagan! Governor Reagan!!” He turned to look at me. “Are you happy with the work you’ve done here today?” I asked.

He gazed at me a moment, shook his head sadly, said, “No, son, I’m not,” then turned and got into the car.

When I filed my radio report from Santa Cruz that afternoon, I related this encounter, then closed by saying: “I have no idea what he meant by that.” And it’s true: at the time, I really was befuddled by that comment. Was he rueful that events had taken such a contentious turn? That seemed unlikely. Had he hoped to broker peace in our time at UCSC? I was literally without clue.

But now, 40 years later, I think I do understand. It’s hard to believe that I could have underestimated Ronald Reagan in 1968: I cut my political eyeteeth in high school by volunteering nights for the Recall Reagan petition drive that gained momentum in 1967, and he was already the object of fear and derision for thousands of UC students, staff, and faculty. But underestimate him I did: Even after the introduction of his resolution that afternoon, I failed to realize that he really, truly wanted to engineer a “takeover” of the University of California by its Regents, and to overturn more than half a century of shared governance between administrators and faculty ... all in the interest of clamping down on student “radicals” and, even more chillingly, limiting the free exchange of ideas and philosophies that he found offputting, or worse.

“Are you happy with your work here today?” What else could he say but “No, son, I’m not”?

Jonathan King, Editor, Berkeleyan

YES, I WAS THERE. I had been teaching at Berkeley since 1962, and 1968 was the year in which — at last — I finally got my tenured associate professorship in the history department. It was, personally, a year of family and of buying a house in Kensington. The rest I watched from afar — with increasing horror, especially the shuddering assassinations of MLK and Bobby Kennedy.

My closest personal encounters were with the politics of Berkeley's 1968-69 "black power" agitation as I endeavored to lecture in Dwinelle with the noise of student demonstrators outside and police tear gas wafting inside. In spring 1969 I left for over a year — in England and India — and so, thankfully, missed the climactic events of People's Park and Cambodia.

Thomas Metcalf, professor emeritus of history

IN THE SUMMER OF 1968 I’d just been hired as an educational counselor at an Ohio Youth Commission facility located on the Ohio State Fairgrounds. The young men I was to counsel were mostly gang members and mostly from the cities. In August our spacious facilities were suddenly transformed as preparations began for the state fair. Music started playing over the fairgrounds P.A., and I remember being knocked out hearing “Hey Jude” for the first time.

I was called into the warden's office. He said our residents will be working at the fair, cleaning up after the animals owned by country boys their same ages. It had been a hot summer full of racial violence, and he told me I had only one job: to make sure there that no racial incident marred the fair. I was working constantly and so did not even hear the headlining Bee Gees, James Brown, and Sly and the Family Stone. I do remember the Chambers Brothers doing a long and blistering “Time Has Come Today.” And I remember my relief when the fair ended without incident.

Victor Edmonds, Educational Technology Services

I MOVED TO BERKELEY on June 19, 1968 — just five days after my 21st birthday. I was transferring to UC as a junior from Shasta College in Redding. I moved into a large studio apartment at 2400 Haste St., at the corner of Haste and Dana. (The building is no longer there.)

I met some interesting people at 2400 Haste. Some I never got to know by name — they were rebels who took up a command post in our basement. Behind the washing machines and the boiler, a radio was set up and the rebels would communicate with various other command posts around Berkeley. When the police and rioters were on Telegraph, the rebels would radio to a command post near Shattuck, and then a throng of people would dash down Shattuck breaking windows. The police would go to stop that riot and the now-abandoned Telegraph Ave. would erupt as a mob started breaking windows. So, back and forth the police would go, while all along our “basement crew” orchestrated the activities.

From 2400 Haste I moved to the top floor of Moe’s bookstore on Telegraph, in an old Victorian building with two floors of studio apartments on top, overlooking Caffe Med. I had a job at Western Variety Store on Telegraph near Durant, making around $1.60 per hour. I had to work so much that the university let me take fewer units per quarter.

I saw many riots and got hit with tear gas and pepper gas a number of times. There was one funny situation I remember in all of that, though. I’d gone to a microbiology lecture in the Life Sciences Building. Someone had thrown a “butyric acid bomb” through the window before our class started, and the huge lecture hall smelled like vomit. Fortunately, we discovered that the farther away from the stage we got, the less objectionable the smell became. Then Dr. Roger Stanier — whom I regarded as a god, as he wrote the microbiology book I’d used in junior college — entered the hall and tried to lecture. He remarked on the smell and the fact that his class was sitting so far away, then, in his proper British accent, said, “At the first sound of a wretch, class is dismissed.” And he fled the lecture hall.

Lilyanne Clark, Public Affairs

I GRADUATED FROM COLLEGE in January 1968. I had just been through a number of family and personal tragedies, so not only did I have the endless possibilities of my life ahead of me, I also had a lot of baggage. It was a time of change.

I was (and am) a died-in-the-wool peacenik, anti-war all the way. Many of my friends went off to fight in Vietnam, and some of the best didn't make it back. Two of those who did come back died 10 to 15 years later from exposure to Agent Orange. I have one friend who still can't go into the woods on a beautiful day without his PTSD kicking in.

All of our lives were changed irrevocably that year, with the assassinations of both Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bobby Kennedy; the ongoing “conflict” in Vietnam and the horror of the My Lai massacre. There were signs of hope, too: the Apollo moon missions; the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, and more. Youthful optimism combined with all of these life-changing events to guide my steps through 1968.

Treacy Malloy, Office of Emergency Preparedness