Berkeleyan

In his lab at Emeryville’s Joint BioEnergy Institute, Berkeley chemical-engineering professor Jay Keasling checks out a culture held by Vernon Wong, left, of Abraham Lincoln High School. At right are Martin Ocampo, of Richmond’s Middle College High School, and Mission High’s Sophia Argueta. (Peg Skorpinski photos) |

Building an energy 'cathedral'

| 21 August 2008

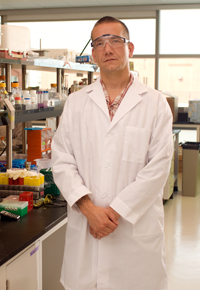

Clem Fortman (www.collinmartin.com photo) |

It’s easy to see why Clem Fortman, a postdoc in the lab of synthetic-biology guru (and Berkeley chemical-engineering professor) Jay Keasling, wanted to open the gates of higher education to promising students who might otherwise never get a foot in the door. A self-described “GED guy,” the impressively tattooed Fortman was kicked out of high school at 17, served a stint in the army, and “goofed off for a number of years” before finally enrolling at the University of Minnesota at the age of 28. Having earned his Ph.D. there in 2006, he’s now on the cutting edge of scientific discovery, working to find a way to turn nonfood substances into cheap, green, domestically produced energy.

This summer, under the auspices of the fledgling High School Biotech Training Program, he was aided in that increasingly critical mission by a half-dozen Bay Area high-schoolers, all of them from families with little or no college experience. The students — four entering their junior years and two soon-to-be seniors — represent the first wave of the pilot project, co-sponsored by the Joint BioEnergy Institute (JBEI), the National Science Foundation, and the campus’s own Synthetic Biology Engineering Research Center, or SynBERC. Organizers hope it will grow into an ongoing program of paid internships for low-income students with college potential who might otherwise have to pass their summers with other teenagers serving customers at McDonald’s.

Instead, the six charter students spent an intensive eight weeks dividing their time between the classroom — where they not only studied chemistry and molecular biology, but learned important life lessons about what it takes to make a career in science — and JBEI’s Emeryville laboratory, where they got hands-on experience in such lab techniques as mass spectrometry, affinity chromatography, and polymerase chain reaction.

It was Sophia Argueta’s love of high-school biology that prompted her to apply for the program. At San Francisco’s Mission High School, she laughs, “we don’t even have a Bunsen burner.” Now she’s at home in a high-tech, 21st-century lab, helping to find an answer to climate change and the energy crisis. The youngest of three kids in a family where no one has been to college, she’d thought about getting a two-year degree, or perhaps becoming a Licensed Vocational Nurse. Her experience this summer has lifted her sights.

A formidable roster of guest speakers, she explains, persuaded her that a bachelor’s degree, or even a master’s, is within her reach. “They would paint a picture of what a university is like,” she says, adding that she missed few opportunities to pepper them with questions about their own GPAs and SAT scores. “So I was like, cool, it’s not impossible, you can get into college. So now I’m inspired. I don’t want to settle for an associate degree now. I want to go higher.”

To Fortman, who hatched the program with fellow postdoc James Carothers, that’s always been the point. “The vast majority of these types of outreach opportunities are focused on the kids who are the straight-A students, the top of their class,” he observes. “And being a GED guy myself, I know there are people out there who aren’t at the top of their class and still have some capacity to do this work — they just don’t have any exposure to the college dream. It’s really not a matter of ability as much as it is opportunity.”

The work itself centers on creating better and more efficient enzymes to degrade cellulose — found in everything from corn stalks to compost and rotting wood — into its constituent sugars, and, ultimately, on efforts to clone a gene that can produce biofuels from readily available nonfood substances instead of from commodities like corn and sugar cane. With oversight from the program’s two postdocs and two credentialed teachers, the students — working with six different organisms in parallel — were taught to isolate degraders by creating cultures in which cellulose is the only carbon source, so that any bacteria unable to live on cellulose essentially starve to death.

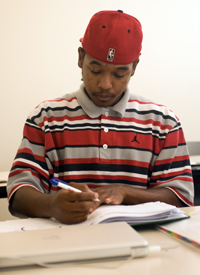

Ian Fagalar, of Pinole Valley High, one of the High School Biotech Training Program’s six charter students. |

Ian Fagalar, who’ll be a senior this fall at Pinole Valley High School, likens the process to locking a vegetarian in a room full of meat. “If he wants to survive,” explains Fagalar, “he’s got to eat the meat.”

Fagalar, whose classroom uniform features a turned-around Red Sox cap, was pondering a football career before he entered the training program. But his brush with world-class science may have changed his plans. “Now,” he says, “I kind of want to get into it.”

Much of the program was devoted to giving the six interns — who attend schools in San Francisco and the urban East Bay — insight into university life. They toured the Berkeley campus, met with undergrads and admissions officials, took part in mock college interviews, and heard presentations from alumni of a half-dozen different colleges. For those contemplating a career in science, there were tours and meetings with employees of biotech firms Novozymes and 23 & Me, as well as bio-pharmaceutical giant Novartis.

For Vernon Wong, entering his senior year at San Franciso’s Abraham Lincoln High, the summer exceeded all his expectations. “The only thing I didn’t like,” he says, “was the BART ride.”

Guided by middle-school science teacher Saber Khan, Ocampo and Berkeley High’s A’Laya Johnson do some classroom research. |

Keasling, Discover magazine’s 2006 “scientist of the year,” says the aim of the program is “to get students interested in science and to see that science can do something really interesting — help solve the energy problem.”

“Solving the energy problem, I heard someone say, is like building a cathedral,” he observed on a recent visit to the Emeryville lab to check on his high-school charges. “We will never see the end of it. They might, but I won’t see the cathedral built. But it’s important to get people interested in science and involved in helping to solve what I think is the world’s biggest challenge.”

Fortman hopes that some local foundations will come through with funding to keep the program going, so that other promising high-schoolers will get the opportunity to contribute. Meanwhile, though, he’s more interested in steering students into higher education.

“The goal is to get these kids into college,” he says. “If they fail miserably on the science, and all of them go to college, that’s 100 percent success.”