Berkeleyan

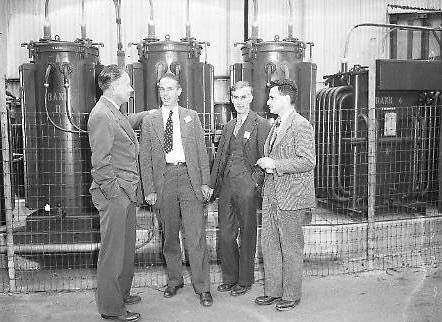

The sketchy notes attached to some Examiner photos raise more questions than they answer. This photo, of a scientific meeting at Berkeley that included such campus notables as E.O. Lawrence (far left) and F.A. Jenkins (to Lawrence’s left), sports a handwritten date of April 7, 1945, identifying the event simply as “Atom Bomb Meeting.” It’s unlikely, though, that that phrase would have been uttered publicly two months before the first top-secret A-bomb test in New Mexico, let alone that a press photographer would have been let in on the chitchat. (Bray) |

San Francisco Examiner archive offers a glimpse of local history

![]()

| 17 September 2008

“Twenty-five Years in Black & White,” a slice of San Francisco Bay Area history from 1935 to 1960, has opened in Doe Library’s Bernice Layne Brown Gallery, featuring more than 100 photos from the Bancroft Library’s Fang Family San Francisco Examiner Archive.

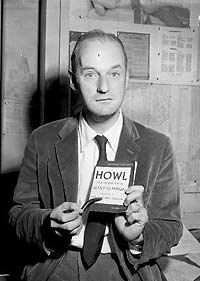

San Francisco poet and publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti at the Hall of Justice in San Francisco, Oct. 3, 1957, after the verdict in the trial over Alan Ginsberg’s Howl. (Gorman) |

Among the images on display are depictions of the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings held at San Francisco City Hall, the Japanese-American internment during World War II, the Great Depression and migrant workers, the controversial Caryl Chessman execution, pro- and anti-Nazi rallies in San Francisco, the signing of the United Nations charter, labor unrest, and an ever-vibrant arts scene.

Each photo was culled from a treasure trove of about 3.5 million photographic negatives and 500,000 prints donated to the Bancroft in 2006 by the daily newspaper’s former owners. The Examiner has published continuously since the mid-1800s, and around the turn of the last century was known as the “Monarch of the Dailies.”

The exhibit was curated by the Bancroft’s Jack von Euw, who says the exhibit offers an “unvarnished and unparalleled” look at Northern California history. “These images are part of our history, visual testimony to quantum leaps in technology, the look of ‘old’ San Francisco, the political investigations driven by the Cold War, and opportunistic politicians playing on the fears of the citizenry.”

In addition to images of major news events, the exhibit chronicles celebrity sightings of stars like Marlon Brando (protesting outside of San Quentin State Prison), opera diva Marian Anderson, Madame Chiang Kai-Shek (arguing for United States support for China against Japan), and newlyweds Joe DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe.

There are also “great pictures of ordinary people doing extraordinary things,” says von Euw. One of his favorites is of workers at San Francisco’s S&S Pie Co. Another is of the “Miss Victory Contest,” whose winners were chosen by coworkers and managers in recognition of their wartime efforts.

The exhibit categories — the war years and their aftermath; fame and fortune; crime and punishment; and people, politics, and places — fell into place as von Euw browsed the archive. Ironically, perhaps, many major issues of the era — immigration and racism, civil liberties and national security, and the death penalty — remain controversial today. “The personalities, the clothes, and the technology change, but the issues are really the same,” says von Euw.

Many exhibit images are being seen for the first time. “So little of what the photographers shot was ever seen beyond the photo editor’s desk,” von Euw says. “We’re looking at prints that have never been seen, even by the photographers themselves.”

Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist and Berkeley alumnus Rube Goldberg donated his archive of more than 55 portfolios of original drawings to the Bancroft Library in 1964. (Needham) |

Von Euw says he appreciates the large, sharp negatives produced by the Graflex camera favored by news photographers of yore. Graflex photographers had to carefully gauge the best time and place for a shot, then hope they could scramble there quickly enough with all of their cumbersome gear.

In recognition of their skill, the exhibit identifies by name the photographers who took the shots. They weren’t always identified in the newspaper, says von Euw, and even in the negative archives they often are listed only by their last names.

Many prints in the Examiner archive are of photos by wire-service photographers, and some were sold to and through commercial outlets. But the negatives are of photos taken by Examiner photographers, representing what von Euw considers the “heart and soul” of the collection.

He didn’t doctor the negatives or clean up scratches to make the images look better because, he says, he wanted to illustrate the archive’s fragility and the need for its preservation. The negatives were scanned and printed on color photographic paper with a LightJet process that gives them an original look.

The monumental task of re-housing prints and stabilizing the at-risk negatives has begun, but without additional funding for preservation, reformatting, and cataloging, says von Euw, much of the archive will remain inaccessible for years to come.

The Brown Gallery is on the first floor of Doe Library. The exhibit is on view until Feb. 28, 2009.