Berkeleyan

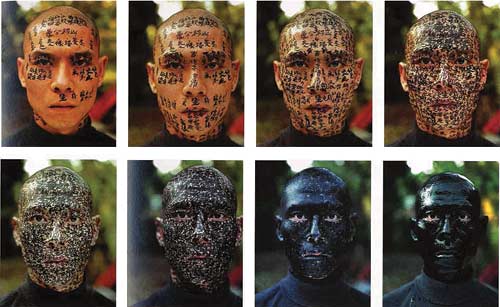

In Family Tree (2000) Zhang Huan had friends paint his entire ancestral history on his face, until he was obliterated by his own history. |

Charting China’s post-Mao history through its art

Berkeley Art Museum’s “Mahjong” takes visitors on a 40-year tour of Chinese creativity

![]()

| 18 September 2008

| Exploring “Mahjong” Most Western travelers wouldn’t think of embarking on a trip to China without a guidebook. Likewise, visitors to “Mahjong” will benefit from one of the many educational programs or guided tours related to the exhibit. |

From the propaganda posters of the Cultural Revolution to modern forms of self-expression, “Mahjong,” Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive’s exhibit of contemporary Chinese art, covers a roiling swath of history. The complexities of Chinese culture are manifold: BAM/PFA has given over nine of the museum’s 10 galleries to the exhibit, and organized three related film series and a host of educational programs and tours to help visitors learn about this recent critical chapter in the history of the world’s most populous nation.

The 196 works on display in “Mahjong” — paintings, photography, sculpture, installations, and video — represent just a slice of this comprehensive private collection of contemporary Chinese art, which includes more than 2,000 pieces. Ironically, it was an outsider who saw the need to amass such a collection.

While once glorified in art, Mao Zedong became a target of artists after his death in 1976. In Wang Guangyi’s Untitled (1986), top, the leader is painted in gray behind a red grid. In a more fanciful treatment, Untitled (Mao/Marilyn) (2005), above, Yu Youhan takes greater liberties. |

Uli Sigg, former ambassador of Switzerland to China, first went to China as a businessman at the start of the country’s “open-door policy” in 1978. Sigg was a longtime collector of Western art. Recognizing that no individuals or institutions were collecting contemporary Chinese art, he stepped in to fill the void in the early 1990s. He bought from artists directly, since no gallery system existed in China at the time.

Under Mao Zedong, artists stopped using art for self-expression due to restrictions imposed by the government. “With the death of Mao, all of a sudden things changed dramatically. Artists had newfound freedom,” says Sigg, who appeared with China authority Orville Schell at the Berkeley Art Museum last week in a conversation about art, censorship, and politics.

Sigg first approached the new art in China with the eye of a collector, but he soon shifted his emphasis. As he writes in the exhbition’s catalog, he originally sought “innovation from a Western point of view,” but then recognized the impossibility of such a task. “When I changed my focus to the overall view relevant to development — what had preoccupied artists over a certain period — I had to revise my criteria,” writes Sigg.

With the bonds of Mao lifted, Chinese artists started to stretch their creative muscles, experimenting with abstract art, formalism, expressionism, and other Western concepts. Sigg estimates that not until the mid-1980s did they begin to find their own language. “These are big steps from a Chinese perspective, though not yet very big steps as seen by the Western contemporary art world,” he says.

To date, the “Mahjong” exhibit — drawing from various works in Sigg’s collection — has appeared in museums in Bern, Switzerland, and Hamburg, Germany. BAM/PFA is the first museum in the United States to host such a wide-reaching collection of contemporary Chinese art. The exhibit’s title is “a metaphor for the way the collection works together,” says Julia White, who, with Lucinda Barnes, BAM/PFA’s chief curator and director of programs and collections, was one of the curators of “Mahjong.”

White and Barnes selected works from Sigg’s large collection to organize each gallery around a unifying theme, such as family, the individual in relationship to society, consumerism, and landscapes. Assembling the groupings was like putting together different sets of Mahjong tiles, says White: “There’s a little bit of chance, there’s a little bit of luck, but there are some rules you need to follow in terms of putting together thematic sets.” With such a prodigious collection, White says, they could have made 20 different shows. “We had the flexibility to arrange the [metaphorical] tiles as we saw fit, the way we wanted to interpret the show, and the ways the artwork wanted to be interpreted.”