Smashing the Berkeley myth

Participatory democracy, individualism, the good life — what could be more all-American?

| 09 October 2008

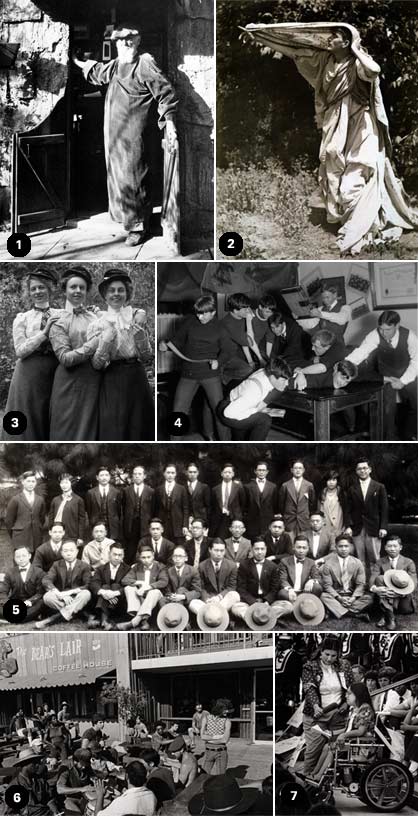

Berkeley's personality was visible — a good half-century before its '60s protests attracted worldwide attention — in the characters who would come to define it, among them architect Bernard Maybeck (1), seen here in typical dress, and poet-naturalist Charles Keeler (2), whose concept of the good life included dressing in Greek robes to illustrate his writings. The University of California plays a starring role in the story: its early high spirits, evident among the young women students in their black "plugs" (3) — hats typically worn by junior men — and in the roughhousing young men of Delta Upsilon (4), both from around 1900; its eclecticism, which as early as the 1920s found expression in the membership of the Chinese Student Club (5); and its traditions, which a generation ago included enthusiastic conga players in Lower Sproul Plaza (6). Town and gown feed Berkeley's brand of politics, which has changed the world: Among many other firsts, rights for the disabled were invented here by many, including Judy Heumann (7), shown giving a late-1970s speech.

(1-2 Courtesy of the Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association, 3-5 Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, 6 Courtesy of Kim Cranney, 7 Courtesy of Jon McNally and the Center for Independent Living)

Berkeley's personality was visible — a good half-century before its '60s protests attracted worldwide attention — in the characters who would come to define it, among them architect Bernard Maybeck (1), seen here in typical dress, and poet-naturalist Charles Keeler (2), whose concept of the good life included dressing in Greek robes to illustrate his writings. The University of California plays a starring role in the story: its early high spirits, evident among the young women students in their black "plugs" (3) — hats typically worn by junior men — and in the roughhousing young men of Delta Upsilon (4), both from around 1900; its eclecticism, which as early as the 1920s found expression in the membership of the Chinese Student Club (5); and its traditions, which a generation ago included enthusiastic conga players in Lower Sproul Plaza (6). Town and gown feed Berkeley's brand of politics, which has changed the world: Among many other firsts, rights for the disabled were invented here by many, including Judy Heumann (7), shown giving a late-1970s speech.

(1-2 Courtesy of the Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association, 3-5 Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, 6 Courtesy of Kim Cranney, 7 Courtesy of Jon McNally and the Center for Independent Living)BERKELEY — If the title of Dave Weinstein’s new book about Berkeley brings to mind space aliens, however friendly and peace-loving, you’d be forgiven. A lot of the world thinks this city and its people came from outer space. But that old sci-fi meme is not remotely what Weinstein, an El Cerrito writer, has in mind.

Nor does he want his title to suggest that the book is a compendium of Berkeley’s trend-setting firsts, though he ticks off many of them (and it’s an impressive list of town/gown accomplishments): The first city to divest from South Africa, to create a citizen police-review panel and a tool-lending library, to provide curbside recycling, to ban Styrofoam, to install curb cuts for people in wheelchairs; the first university to come up with the atom smasher, nuclear medicine, and the wetsuit. And there are more.

Weinstein has a more provocative point to make, nothing less than the demolition of the national myth that Berkeley is a place that’s not really part of the United States.

“Has there ever been a town more all-American?” he asks in his introduction. “Do Americans believe in individualism, living the good life, and participatory democracy? That’s what Berkeley is all about. And has there ever been a city in America in which religion and spirituality have more effectively served as forces for social change?”

It Came From Berkeley (Gibbs Smith, 2008) very literally means that Berkeley, simply by being Berkeley, bubbling and boiling with an active political, intellectual, spiritual, and environmental life, has in Weinstein’s view had an impact clear across America.

He’s very serious, which doesn’t keep the book from being engaging and readable. The material is broken down into 61 palatable bites, in 1970s-era typography, like “How Berkeley Spurned Spanking” for a piece about the city’s progressive police force, or “How Berkeley Became Asian” for one on racial politics, or “How Berkeley Women Grew Uppity” for a piece on feminist politics.

Weinstein traces the same story that Berkeley City College historian Charles Wollenberg told in his book Berkeley: A City in History, which came out earlier this year. But Weinstein’s book depends much more heavily on photos, pulled from the holdings of Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, other campus libraries, as well as the collections of the Berkeley Historical Association, the Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association, the Oakland Museum of California, and private photographers.

Like Wollenberg, Weinstein says that Berkeley would not be what it is without the university — but that’s not enough to explain Berkeley.

“Berkeley is a place that, when people think about it, they immediately have an idea of something special, something that means more than just a certain place,” he says. “When you say Palo Alto, it doesn’t have the same meaning. Not Ann Arbor. But Berkeley really came to have a meaning.”

That meaning developed early and naturally, a story Weinstein tells through some of its main characters, people like poet Charles Keeler and architect Bernard Maybeck. Though Maybeck may be better-known these days, it was Keeler, Weinstein says, who came up with the idea of Berkeley as a place where people could live the good life.

Dave Weinstein (Carol Ness photo)

Dave Weinstein (Carol Ness photo)“Not as it’s defined in Blackhawk or Malibu — not just about money or living luxuriously,” Weinstein says. “It’s about the arts, tying science and art together, getting religions and spirituality in there.” The values that have defined Berkeley are bedrock American values: participatory democracy and individualism, the latter of which Weinstein defines as “the ability of the individual to really play a role in the community, and to fight against any attempt to tell them what to do.”

The theme runs from Berkeley’s beginnings through its long Republican incarnation, into the modern Democratic era and right up to the present-day fights over land use and Marine recruiting. The excesses may be what attract national attention, Weinstein says, but they’re just the most visible part of what makes Berkeley Berkeley.

“I wish America was more like Berkeley,” Weinstein says.

For more information about It Came From Berkeley, visit www.davidsweinstein.com.