Obituary

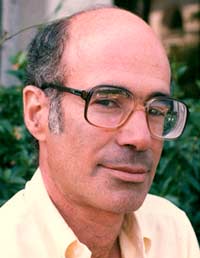

David Freedman

22 October 2008

BERKELEY — David A. Freedman, a professor of statistics who fought for three decades to keep the United States census on a firm statistical foundation, died Friday, Oct. 17, of bone cancer at his home in Berkeley. He was 70.

BERKELEY — David A. Freedman, a professor of statistics who fought for three decades to keep the United States census on a firm statistical foundation, died Friday, Oct. 17, of bone cancer at his home in Berkeley. He was 70.

Throughout his career, Freedman made major contributions to the theory and teaching of statistics. He also had a broad impact on the application of statistics to important medical, social, legal, and public-policy issues, including clinical drug trials, epidemiologic studies, economic models, interpretation of scientific experiments, statistical evidence in the courtroom, and adjustments to the census.

“David transformed the practice of applied statistics as it is directed toward litigation, toward congressional action, and toward public policy,” said longtime friend and colleague Kenneth Wachter, a Berkeley professor of demography and statistics. “The prevailing mode when he began working was to rely on hypothetical models with assumptions sometimes driven by mathematical convenience, which were fine for theoretic work but, when carried over to applications in the policy arena, gave conclusions that were often fanciful or driven by the prejudices or presuppositions of the statisticians testifying or contributing.”

Wrote James Robins, professor of epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health, in 2002: “Not only has David, since his early 20s, been recognized as one of the world’s leading mathematical statisticians, but he has also assumed the mantle as the skeptical conscience of statistics as it is applied to important scientific, policy, and legal issues.” Freedman clarified the assumptions underlying a wide variety of statistical models and revealed how sensitive conclusions can be to violations of those assumptions — regardless of the quality of the data. “By distinguishing proposals based on hypothetical modeling from proposals grounded in empirically established observations, he developed a firmer basis for applying statistics to policy,” Wachter said.

His legacy, said Berkeley colleague Philip Stark, professor of statistics, is “demystifying and debunking many of the tools people use in social science and elsewhere to try to draw inferences.” Even today, “there is a lot of muddled thinking and blind reliance on methodology — almost a religious belief that methods give truth — without looking carefully at the assumptions of the methodology. David contributed enormously to the clarity and rigor and circumspection” in the field of applied statistics.

Both Freedman and Wachter testified before Congress and the courts against adjustments to the 1980 and 1990 censuses proposed to make up for perceived geographical and ethnic undercounts. A 1990 lawsuit to force the Department of Commerce, which oversees the decennial census, to make such adjustments was taken all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which in 1996 sided unanimously with the Commerce Department and Freedman’s analysis. The department won a similar lawsuit in 1980.

“The census turns out to be remarkably good, despite the generally bad press reviews,” Freedman and Wachter wrote in a 2001 paper published in the journal Society. “Statistical adjustment is unlikely to improve the accuracy, because adjustment can easily put in more error than it takes out.”

Freedman was viewed by many as the world’s leading forensic statistician, Stark said. He testified as an expert witness on statistics in law cases that involved employment discrimination, fair loan practices, voting rights, duplicate signatures on petitions, railroad taxation, ecological inference, flight patterns of golf balls, price-scanner errors, and sampling techniques. He worked as a consultant for the Carnegie Commission, the City of San Francisco, and the Federal Reserve, as well as the U.S. departments of energy, treasury, justice, and commerce. He was often called by the media to comment on the statistical validity of studies.

Freedman was deeply committed to improving the quality of statistics education, said colleague David Collier, a Berkeley professor of political science. As chair of Berkeley’s statistics department from 1981 to 1986, Freedman and his colleague Peter Bickel reorganized undergraduate teaching to emphasize the applied aspects of statistics, and they instituted the Statistical Consulting Service to serve campus researchers and to provide real-world experience for statistics students.

“Freedman’s transition from being a mathematical statistician to a creative practitioner of applied statistics occurred in part, by his own account, in response to the challenges of undergraduate teaching on the Berkeley campus,” Collier said. “His students were bored with statistics courses and with the abstracted examples that were standard fare in textbooks,” leading Freedman to dig up practical examples in many applied areas.

Wachter noted that, thanks to the late Jerzy Neyman, who founded the field of modern statistics and Berkeley’s statistics department, “Berkeley was famous for statistical theory. If you wanted to do theory, Berkeley was the place, whereas applied work was given short shrift. David and Peter Bickel undertook transforming the department as the wave of theory had run its course to emphasize high-level, mathematically informed applied work, since significant theoretical work now comes in response to applied problems.”

Freedman wrote six textbooks, including the highly regarded undergraduate text Statistics with co-authors Robert Pisani and Roger Purves; the book is now in its fourth edition.

Born in Montreal, Canada, on March 5, 1938, Freedman obtained his B.Sc. from McGill University in 1958 and his Ph.D. from Princeton University in 1960. After a year at Imperial College London on a Canada Council fellowship, he joined the Berkeley statistics department in 1961 as a lecturer, and was appointed to the faculty in 1962. In addition to stints as vice chair and chair of the statistics department, he also was a Miller Fellow in 1990 and an Alfred Sloan Fellow from 1964-66. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Freedman is survived by his wife, Janet Macher; stepmother Charlotte Freedman of Montreal, Canada; two children, Joshua of Corralitos and Deborah Freedman Lustig of Walnut Creek; his first wife, Shanna Helen (Wittenberg) Swan of Rochester, N.Y.; and four grandchildren.

A campus memorial is planned for December. In lieu of flowers, donations in memory of David Freedman can be made to the UC Berkeley Foundation, c/o University Relations, 2080 Addison St., Berkeley, CA 94720-4200.

—Robert Sanders