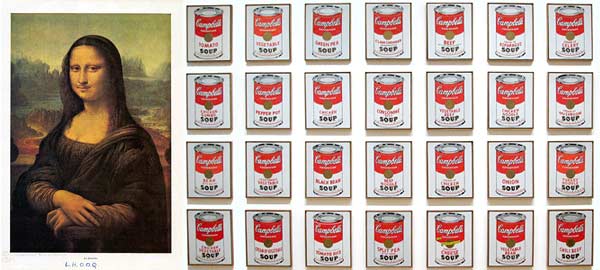

Artistic appropriation of the works of others is nothing terribly new, though the advent of digital media has made the practice more ubiquitous as well as technically easier to accomplish. Earlier examples include Marcel Duchamps’ goateed-and-mustachioed Mona Lisa parody, L.H.O.O.Q., from 1919 (left), and Andy Warhol’s iconic Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962).

Artistic appropriation of the works of others is nothing terribly new, though the advent of digital media has made the practice more ubiquitous as well as technically easier to accomplish. Earlier examples include Marcel Duchamps’ goateed-and-mustachioed Mona Lisa parody, L.H.O.O.Q., from 1919 (left), and Andy Warhol’s iconic Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962).He who steals my artwork steals . . . what, exactly?

One side in this debate claims that appropriating visual imagery in the digital age is a legitimate artistic enterprise; the other insists it’s the illegal use of another’s intellectual property. It’s one question among many to be considered at a campus conference next week

| 29 October 2008

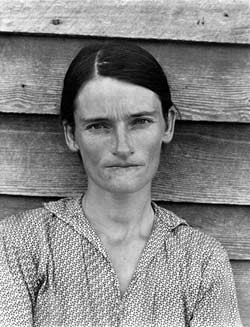

BERKELEY — In 1979, an artist named Sherrie Levine took some photos of Depression-era Alabama sharecroppers — not by lugging her camera gear to an Old Sharecroppers’ Home on visiting day, but by photographing existing photographs. And not just any photos: these were well-known images captured by Walker Evans, the much-lauded chronicler (along with writer James Agee) of poverty and hopelessness in mid-1930s rural Alabama. Levine had located the photos in an exhibition catalog.

Above is a photo of a photo of a photo: Michael Mandiberg’s “authentic” copy of Sherrie Levine’s 1979 photo of Walker Evans’ 1936 portrait of Allie Mae Burroughs, an Alabama sharecropper.

Above is a photo of a photo of a photo: Michael Mandiberg’s “authentic” copy of Sherrie Levine’s 1979 photo of Walker Evans’ 1936 portrait of Allie Mae Burroughs, an Alabama sharecropper.Levine’s bold appropriation of Walker’s world-famous images, familiar to generations since their publication in 1941’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, became “a landmark of postmodernism, both praised and attacked as a feminist hijacking of patriarchal authority, a critique of the commodification of art, and an elegy on the death of modernism,” according to materials about Levine’s series published on the website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which now owns the work.

Comes now the digital age and New York artist Michael Mandiberg, who has photographed Levine’s photographic copies of Walker’s catalog images and posted the results online at AfterSherrieLevine.com for anyone to download and print. Mandiberg also provides a downloadable “certificate of authenticity” specifying that images printed and framed according to precise directions are genuine Mandiberg works.

By these means, Mandiberg writes, “I have taken a strong step towards creating an art object that has cultural value, but little or no economic value.” His bold appropriation, he says, is intended to facilitate the dissemination of these images “as a comment on how we come to know information in this burgeoning digital age.”

Digitization, which enables both the exact replication of artworks, famous and otherwise, and their worldwide dissemination, has added new layers of complexity to legal, artistic, and ethical discussions around the issue of artistic appropriation.

To discuss those issues, more than a dozen artists (including Mandiberg), curators, legal experts, art historians, and digital-media activists will speak at a two-day campus conference next week that’s all about traversing this cutting-edge terrain. “Takeovers & Makeovers: Artistic Appropriation, Fair Use, and Copyright in the Digital Age” will take place Friday and Saturday, Nov. 7 and 8, in the Berkeley Art Museum auditorium. It is free and open to the public. (The conference schedule is online.)

Conference co-organizer Kris Paulsen, a Ph.D. candidate in rhetoric, isn’t prepared to declare that Mandiberg’s artistic appropriation was fully legal. “That’s up for debate,” she says, noting that her desire “isn’t to point out what should be legal or not, but to discuss the problems in commenting on the culture” that are raised in the digital age. As the Mandiberg project demonstrates, digital media make it easy for artists to appropriate, borrow, sample — or steal, depending on how you look at it — other people’s work in the interest of commenting on it, taking the ideas in a new direction, parodying them, or making a statement about things like authorship, authenticity, ownership, or the culture itself.

Copyright law, meanwhile, though it allows artists — as well as corporations — to protect themselves and their livelihoods by protecting their intellectual property, can also shackle freedom of expression. And finding the balance between the two effects is an ongoing legal and cultural struggle.

Though Napster and YouTube have made music and video the modern flashpoints of conflict between digital creativity and copyright, the issues play out in all the same ways for visual artists too, Paulsen says — even though, until recently, the art world has tended to treat appropriation as a philosophical question more than a legal one. “We’re interested in thinking about the nuts-and-bolts legal questions that affect artistic production,” she says. “Usually this doesn’t enter into the equation.”

Another issue is that so much in the world is trademarked or copyrighted nowadays that photos or video shot in the street almost can’t avoid having copyrighted images in them, adorning objects such as signs or buildings.

“The idea that anyone who owns the trademark can stop you from commenting on it is a very dangerous place to get into,” Paulsen contends. Though a court may eventually decide that an appropriation is a “fair use” of another’s material, “that doesn’t mean you can’t be sued, and most people don’t have the money to take on Disney or Viacom.”

Fair use is a legal concept that condones appropriation if, for example, the borrowed work is transformed into something new, or at least transformed enough. Though judicial discretion is key in such judgments, and other tests must be applied to each case, parody and criticism are generally considered to meet fair-use restrictions.

When lawsuits loom

But in one famous case, artist Jeff Koons’ wood sculpture String of Puppies, which rendered in three dimensions an image taken from a postcard, was deemed not transformed enough to be considered a protected fair use. The court decision “had a really devastating effect on artists,” Paulsen says.

And now digital media raises new questions. “Koons didn’t make an exact copy — he made a sculpture of an image,” Paulsen points out before asking, “What happens when you take the image exactly as it is, with nothing but copying and pasting between the original and its appropriation?” The looming threat of lawsuits is enough to create a culture of fear in the art world, she adds, one that can lead to self-censorship as effectively as litigation itself.

The challenge of reconciling the artistic impulse to appropriation with the constraints of copyright law will be the focus of next week’s “Takeovers & Makeovers” conference, among whose presenters will be members of San Francisco’s Billboard Liberation Front, who will speak on “Media Banditry in the Digital Age.”

The challenge of reconciling the artistic impulse to appropriation with the constraints of copyright law will be the focus of next week’s “Takeovers & Makeovers” conference, among whose presenters will be members of San Francisco’s Billboard Liberation Front, who will speak on “Media Banditry in the Digital Age.”A Friday-morning conference panel will take this issue on directly. “Best Practices for the Arts/Myths of Fair Use” promises a discussion between artist Mandiberg and two experts in the field of digital technology and intellectual-property law.

One of them is Jason Schultz, acting director of Berkeley’s multidisciplinary Samuelson Law, Technology, and Public Policy Clinic, which participates in Chilling Effects (chillingeffects.org), an online resource center run by several top universities to help the public deal with legal issues that spring from the Internet, including copyright conflicts.

The digital revolution also has pitched museum curators into tricky territory, says Berkeley Art Museum (BAM) digital-media director and adjunct curator Richard Rinehart, who says they are caught between artists/creators and the consumers of their art — students and publishers. He’ll speak on a Friday panel devoted to this subject.

“We want to provide research access to our collection,” says Rinehart. “For example, we can take photos [of artworks] and put them on the Web.” But should a museum do so merely because it can? What if curators can’t find artists to ask their permission. What if the artists are no longer living?

“Can we put it on the Web because we’re part of a university, and it’s okay for non-profit educational use?” he asks rhetorically. Maybe so — but if a museum does that, its valued relationship with “the community of artists” might well be jeopardized, Rinehart says. And if it doesn’t, it might anger the students and researchers who depend on it.

“We end up being more conservative than the law permits,” Rinehart acknowledges.

Other considerations may be raised by an artwork itself. In a new BAM exhibit called “Gas Zappers,” artist Kenneth Tin-Kin Hung, in Rinehart’s words, “basically steals all these images from all over the Internet” and incorporates them into an online game that takes on the issue of global warming.

“And here we are presenting it at Berkeley,” Rinehart continues. “We have to think not only about the risk the artist is incurring, but whether we’re somehow putting the campus at risk as well.”

Another example is New York artist Mark Napier’s Shredder 1.0, a piece Rinehart presents to students in his digital-media class. It’s a website where a user enters the URL of another site. The “Shredder” goes to that page, mashes up what’s there, and recombines it all in a new sliced-and-diced image.

Muses Rinehart: “What if it shreds the Stanford website? And Stanford comes to us, and we say, ‘it’s part of an artwork.’ And they say, ‘We don’t care, it’s ours.’ From our perspective we’re just collecting these works and presenting them. So what’s our liability? They didn’t have to worry about these things in Leonardo’s day.”

In the end, Rinehart says, such questions boil down to one principle:

“It’s not just about the letter of the law, about protecting our money through avoiding legal risk and liability. We’re all about the spirit of the law. We’re concerned about the ethics of everything. Maybe we’ll decide that in this age of reproducibility this kind of work needs to be made, and we need to create a safe public space for it.”