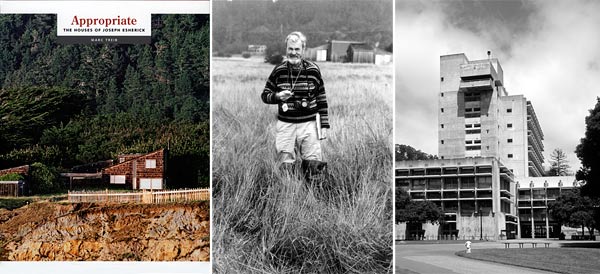

Professor Emeritus Marc Treib’s new book (left) addresses the life and architecture of the late Professor Joseph Esherick (center, at Sea Ranch, one of his most important works; Esherick helped design Berkelely’s Wurster Hall (right), whose stark form inspires both love and hate 44 years after it was built. (Left to right: William Stout Publishers, George Maslach, Marc Treib)

Professor Emeritus Marc Treib’s new book (left) addresses the life and architecture of the late Professor Joseph Esherick (center, at Sea Ranch, one of his most important works; Esherick helped design Berkelely’s Wurster Hall (right), whose stark form inspires both love and hate 44 years after it was built. (Left to right: William Stout Publishers, George Maslach, Marc Treib)A Bay Region master

The architecture of Joseph Esherick finally gets its due

| 05 November 2008

BERKELEY — The late Professor Joseph Esherick may be the most accomplished Bay Area architect you’ve never heard of.

Say the name Bernard Maybeck and the early-20th-century architect’s Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco, or his many Craftsman-style homes around Berkeley, spring to mind. Say Julia Morgan and up are likely to pop thoughts of the Hearst Greek Theatre near Memorial Stadium, or the Berkeley City Club building on Durant Avenue — not to mention San Simeon, the castle she built for William Randolph Hearst, perennially rated among California’s top tourist attractions.

But how many people, hearing Esherick’s name, will conjure up The Sea Ranch, the coastal enclave near Gualala that defined a new, ecologically informed, and space-defined style of architecture well ahead of its time? Or the Cannery in San Francisco, or Monterey Bay Aquarium, or the many innovative and livable homes Esherick and his firm built in Berkeley and all over the Bay Area?

If anything, Esherick may be best remembered as one of the creators of UC Berkeley’s Wurster Hall, the looming, stark concrete hulk that is still controversial 44 years after its construction. Wurster was built to house the College of Environmental Design, which includes the architecture department where Esherick taught from 1952 until his retirement in 1985.

Marc Treib (Courtesy Marc Treib)

Marc Treib (Courtesy Marc Treib)Esherick himself liked to joke that anyone trying to find Wur-ster should simply “ask any policeman or old lady for the ugliest building on campus and they’ll point you right to it,” writes Marc Treib, emeritus professor of architecture, in his recent book on his former colleague. Appropriate: The Houses of Joseph Esherick (William Stout Publishers, 2008) is the first major work about the architect and his contributions.

Treib focuses on Esherick-designed homes to make the case that he was “a major player in the architecture of San Francisco beginning in the 1940s, and its pre-eminent architect during the 1960s through the 1980s — known and widely published nationally and internationally, but all but lost to the current generation.”

Treib takes his title, Appropriate, from what he defines as Esherick’s most distinguishing trait, especially with his homes: He designed buildings that were appropriate to their site and created spaces that fit the way people would live inside them.

In a 1947 New Yorker column that rocked the East Coast-oriented architectural world at the time, architectural and social historian Lewis Mumford famously lauded this approach as the Bay Region Style, a mid-century follow-up to Maybeck and Morgan and their elegant but simple, sometimes rustic designs.

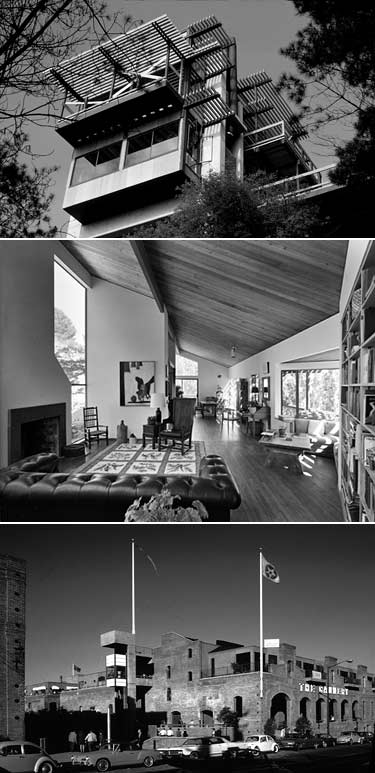

The bold Bermak House, on a difficult site in the Oakland hills (top, 1962); living-dining space in the Romano House in Kentfield (center, 1969) shows classic Esherick use of windows; the Cannery in San Francisco (bottom, 1967) is one of the architect’s best-known and most public works. (Top to bottom: Roy Flamm, EHDD, Robert Brandeis, EHDD, Marc Treib)

The bold Bermak House, on a difficult site in the Oakland hills (top, 1962); living-dining space in the Romano House in Kentfield (center, 1969) shows classic Esherick use of windows; the Cannery in San Francisco (bottom, 1967) is one of the architect’s best-known and most public works. (Top to bottom: Roy Flamm, EHDD, Robert Brandeis, EHDD, Marc Treib)Modern achitecture’s challenge, Mumford wrote, was to reconcile the lessons of “science and the machine with human wants and desires, with full regard for the setting of nature, the climate and topography and vegetation.” Bay Region architecture met the challenge, he concluded.

And Esherick, says Treib, was one of the most successful in its expression.

After graduating from the University of Pennsylvania, Esherick arrived in San Francisco from Philadelphia in 1938, lured by the hope of working with William Wurster, a Maybeck protégé who was then one of the top California architects working in the modern style. (Wurster later became the first dean of the College of Environmental Design.) Esherick didn’t end up working for Wurster, as Treib tells the tale, but settled in with his rival, Gardner Dailey, and quickly made his mark.

After World War II he opened his own firm, which evolved into Esherick, Homsey, Dodge, and Davis (EHDD) with the addition of Berkeley graduates George Homsey, Peter Dodge, and Chuck Davis. The firm, which still maintains a practice in San Francisco, designed large projects — such as the Cannery and Stevenson College at UC Santa Cruz — as well as many private homes.

A key project was The Sea Ranch, the community of second homes on the Sonoma County coast. Starting in the early 1960s, Esherick and his team worked closely with landscape architect Lawrence Halprin to create a development that fit the shape of the terrain; the planners also took into consideration the site’s geology, flora, fauna, and patterns of sun, wind, and rain, as well as traditional uses of the land.

The original Sea Ranch houses were small, clustered, and built of simple materials. Photos of the Hedgerow Houses there demonstrate the style vividly: the slant of the low roofs echoes the wind-bent cypress trees; the angles and windows capture the afternoon light reflecting off the ocean.

Though sharing aesthetic and design principles, the homes were no ticky-tacky boxes. Each was designed for its particular site and the family that would dwell there.

Among the homes that Esherick designed was one for the family of Christina Maslach, now Berkeley’s vice chancellor for teaching and learning. Esherick also designed an 850-square-foot home for his own family.

Of all of Esherick’s work, Sea Ranch was the most influential, Treib maintains.

“At the time, architects throughout the country, if not the world, were copying that architecture — even in places it shouldn’t have been,” he says. (Later additions to Sea Ranch failed to adhere to Esherick’s principles, he adds.)

Other than Sea Ranch, though, Esherick’s approach to design allowed for such variety and flexibility that it’s tough to look around and spot “an Esherick.”

“He wasn’t a major form-giver. He wasn’t a Frank Lloyd Wright. He didn’t do frivolous shapes — his architecture was quieter, and more about living and use, than flashy designs to be reproduced in the professional journals,” Treib says.

That’s one of the big reasons, in Treib’s view, that Esherick’s contributions haven’t received more attention — even though he won the American Institute of Architects gold medal, the profession’s highest honor.

The spiral staircase in San Francisco’s Larsen House (left, 1962) floats freely in space. (Marc Treib)

The spiral staircase in San Francisco’s Larsen House (left, 1962) floats freely in space. (Marc Treib)Two other reasons stand out, he adds. Esherick’s designs are all about space, which is difficult to capture in photographs, not about form, which is more photogenic. And Esherick’s homes were occupied by real people, whose well-lived-in furnishings didn’t lend themselves to glossy home-design or architectural magazines.

“Esherick was part of a sensibility, he didn’t really originate it, though he was one of the most influential architects then working in Northern California,” Treib adds.

Esherick and Treib overlapped in Berkeley’s architecture department; in fact, Esherick was Treib’s thesis adviser in the late 1960s. Treib earned master’s degrees in architecture and design before joining the faculty in 1968.

The book on Esherick is the latest in the Berkeley/Design/Books series, which Treib instigated for CED before retiring last year. The series, published by William Stout (stoutbooks.com), draws on the extensive holdings of Berkeley’s Environmental Design Archives (ced.berkeley.edu/cedarchives), curated by Waverly Lowell.

Appropriate is the series’ fourth title. Treib plumbed the archives’ Esherick papers for the book, and relied on an oral history of the architect conducted by the Bancroft Library’s Regional Oral History Office.

Treib, who designs and produces all the books in the series, also wrote one other, The Donnell and Eckbo Gardens: Modern California Masterworks. A fifth book, by Lowell, will explore Greenwood Common, the mid-century cluster of modern homes above the Rose Walk in North Berkeley.

In addition to his Esherick book, Treib edited two other books that have come out in the last year, both based on symposia he planned: Representing Landscape Architecture and Drawing/Thinking: Confronting an Elec-tronic Age, both published by Routledge.