The Mark Twain Project stretches out

New digs mean not just more room for researchers, but better conditions for archival storage

| 22 January 2009

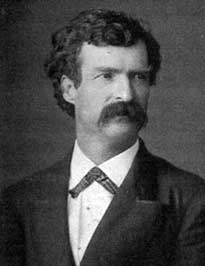

Samuel Clemens

Samuel Clemens BERKELEY — If Samuel Clemens had lived in the age of Twitter and Facebook, his nonstop outpouring of observations about American life would fit neatly on a medium-size hard drive.

Clemens, however, applied pen and pencil to paper when he wanted to jot down his ideas, write and rewrite his manuscripts, and turn out thousands of letters, notebooks, and other documents — low-tech, relatively delicate items that need both space and tender loving care to preserve for researchers, literary historians, and just plain fans of the writer better known as Mark Twain.

Now they have plenty of both, with the expansion of the Mark Twain Papers and Project's digs on the fourth floor of Berkeley's newly renovated Bancroft Library.

"Before, we were so jammed up with file cabinets and piles of papers and books that people who came to visit us really didn't have a place to work," says Bob Hirst, who watched the old space fill to overflowing in his 28 years as curator and general editor of the Twain collection.

Valuable letters, manuscripts, first editions, photos, and ephemera, all pocked with Twain's witticisms and drawings, languished in less than optimal conditions.

"People would come and ask me, where's the air conditioning? Where's the temperature and humidity control? And I'd point to that window," Hirst says, gesturing across his corner office. Now, though, says Hirst, "The safety and care we can extend to the manuscripts is greatly improved."

The papers — the world's largest collection of Clemens' work — now have a vault of their own, a windowless, locked room equipped with climate controls so new they still need tweaking. The collection's move to temporary quarters during the renovation, and then back, allowed the papers to be organized and filed in acid-free folders and boxes.

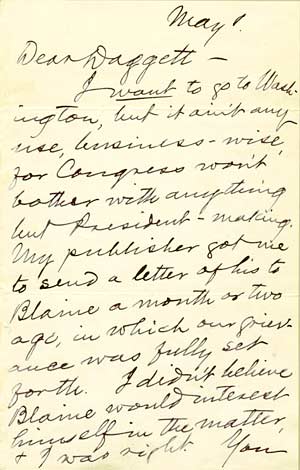

Visitors to the Mark Twain Project's website can zoom in on selected pieces of the author's correspondence, such as this note complaining about counterfeit editions of his work.

Visitors to the Mark Twain Project's website can zoom in on selected pieces of the author's correspondence, such as this note complaining about counterfeit editions of his work.Securely stored are some 10,000 of Clemens' handwritten letters to his wife, publishers, and friends (out of the 50,000 he's estimated to have written in his lifetime), as well as letters written to him, all but four of the small, leather-bound notebooks he kept yearly, plus first and rare editions of his books. (An exhibit of items from the collection is on public display in the Bancroft's new gallery, just inside the front entrance.)

For researchers, the new quarters mean space to spread out in a new reading room stocked with cherrywood tables and computer hookups. Most will work with photocopies, though a few will be granted permission to view the originals.

For Hirst and his seven staffers, the renovation has created offices where they can do their work — continuing to build the collection, and mining the papers in minute detail to build historically and literarily accurate versions of Clemens' prodigious output.

So far they've produced some 30 books, all published by UC Press, including the only authoritative text of Twain's masterwork, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and collections of his letters (through 1880 to date).

The project's next major work will be Clemens' definitive autobiography, due out in 2010, 100 years after his death and 175 after his birth. The author left behind an enormous pile of manuscripts and dictated typescripts about his life, revised many times — but no clear plan for putting them together.

He gave up on the idea of a chronological accounting. "His rationale was that cradle-to-grave plans … have a way of preventing you from telling the truth," Hirst says. "The thought behind dictating, and changing his mind when he wants to, is that maybe the truth will emerge more clearly."

Before then, a book of 24 previously unpublished Twain writings, Who Is Mark Twain?, is due out this April from Harper Studio. In a preview, one of the pieces, "The Privilege of the Grave," appeared in the Dec. 22-29 edition of The New Yorker magazine.

The Twain papers will also continue their march into the digital age. So far, about 2,300 letters written between 1853 and 1880 have been put online in a searchable database (see marktwain

project.org). In many cases, both annotated texts and facsimiles of the actual letters are online.

Come spring, the project's latest annotated edition of Huck Finn will go up online too. And when the autobiography comes out, it will be published on paper and on the Web simultaneously, Hirst says, noting that "the real appeal of this is that it produces universal access to the things people ought to have."

So far, though, having the archive online hasn't reduced the number of researchers making the pilgrimage to the Bancroft. "People want to come and see for themselves," explains Hirst. "They want to see the original."