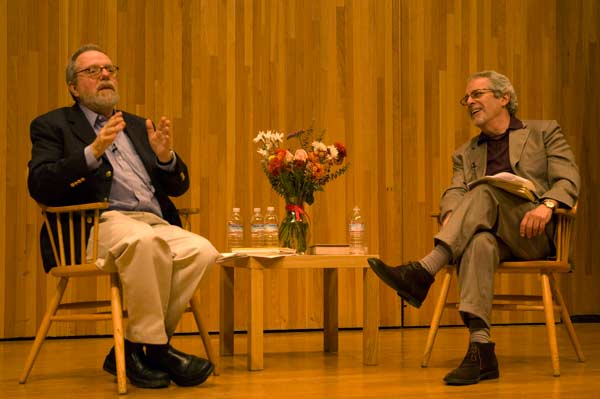

David Denby, left, and Geoffrey Nunberg engaged in a respectful, non-snarky discourse about ... well ... snark. (Wendy Edelstein photo)

David Denby, left, and Geoffrey Nunberg engaged in a respectful, non-snarky discourse about ... well ... snark. (Wendy Edelstein photo)Hunting for snark

In a campus conversation with linguist Geoffrey Nunberg, New Yorker critic David Denby takes on modern-day barb-slingers

| 05 February 2009

BERKELEY — Benjamin Button, the heavily Oscar-nominated film, is "beautifully crafted but boring," pronounced New Yorker film critic David Denby last week during a campus visit to promote Snark, his new book.

If you mistake the above comment for snark, which Denby rails against for 122 pages in his short tome, you're to be forgiven: Spotting snark is not always easy. Are Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert snark-peddlers? Nope. "Even when pecking at a victim's tender spots, they also manage to defend civic virtue four times a week," writes Denby of Comedy Central's pseudo-news stars.

If they're not snarky, who is? In the same late-night universe, Denby observes in his book, David Letterman is, but Jay Leno isn't. For Denby, snark lacks sophistication and subtlety. Last Thursday night, in Sibley Auditorium, he made his case against verbal and penned poison arrows in a conversation with Geoffrey Nunberg, adjunct professor at the School of Information and commentator on matters linguistic for NPR's Fresh Air. Snark "doesn't engage," Denby told the Berkeley audience. "It's bulimic. It doesn't digest. It takes something, turns it into caricature, gives it a little twist of humor, and throws it back. Not only is it not thoughtful, it's finally cynical and stupid."

If they're not snarky, who is? In the same late-night universe, Denby observes in his book, David Letterman is, but Jay Leno isn't. For Denby, snark lacks sophistication and subtlety. Last Thursday night, in Sibley Auditorium, he made his case against verbal and penned poison arrows in a conversation with Geoffrey Nunberg, adjunct professor at the School of Information and commentator on matters linguistic for NPR's Fresh Air. Snark "doesn't engage," Denby told the Berkeley audience. "It's bulimic. It doesn't digest. It takes something, turns it into caricature, gives it a little twist of humor, and throws it back. Not only is it not thoughtful, it's finally cynical and stupid."

In his book, subtitled "It's mean, it's personal, and it's ruining our conversation," Denby broadly traces the history of snark, starting with Roman-era roasts and the "ravaging, wildly embittered, cruelly funny" writings of Juvenal (circa 55 A.D.) and working his way up to the 1960s-era British satirical rag Private Eye, Tom Wolfe's pointed attacks on New York's radical elite a decade later, and Spy magazine's envious swipes at Manhattan's power brokers.

Although snark's origins date back to Roman times, it wasn't until 1874 that Lewis Carroll invented the actual word when a nonsensical line of verse popped into his head during a walk: "For the Snark was a Boojum, you see." In Carroll's mock-epic poem, "The Hunting of the Snark," those beastly Boojums obliterated unsuspecting people on contact. In other words, snark can be deadly.

A matter of perspective?

"Has the nastiness, snarkiness, and vituperation been out there" all along, wondered Nunberg. Perhaps, with the advent of the Internet, snark's ubiquity may have more to do with the medium than with a real change in the zeitgeist, he suggested.

The Internet, responded Denby, is an "extraordinary revolution in democracy, the greatest thing since the ballot." But at the same time as it has led to an "explosion of creativity, warmth, generosity" as well as a "sharing of and generation of information," the medium also provides a means for expressing "bilious hatred and prejudice."

Some of that vitriol is posted under a byline. Denby singles out New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd as the best-known purveyor of snark: Though she possesses "enormous verbal abilities" and is "genuinely funny," Dowd lacks political commitment and bases her attacks on style rather than ideas, he charged, characterizing her pursuit of Hillary Clinton during the Democratic primaries as "vicious" at times. She trivialized Clinton's campaign for the presidency, judging it to solely be about vanity, personal power, and ambition.

Denby also called Dowd to task for ridiculing then-candidate Barack Obama, whom she called "effeminate and diffident." Denby wondered: "Is she mad? This is one of the most politically ambitious men of the last hundred years. She only judges by the surface, so she got him wrong."

Bigger fish to fry

Denby's larger concerns center on the "enormous changes in journalism" transpiring as more newspapers shift from print to the Web. He worries that this shift might diminish some forms of journalism — investigative reporting, well-reported sports stories, arts criticism — or even cause them to disappear.

Experienced journalists are panicked, he says, because they know the newspaper business model isn't working any more, and some resort to glibness to hold onto their younger readers. Younger writers, meanwhile, get snarky in their posts to such alternative-media blogs as Gawker, Defamer, or Wonkette, in order to get a toehold in their new profession.

One casualty of this migration to the Web might be the construction of "a centralized narrative" about events in politics, the economy, culture, and foreign affairs, to be encountered in the nation's leading newspapers and news magazines. If economics force those publications to become Web-only presences, they will likely become "part of the general clamor," fears Denby, and in that well of competing voices, snark could become even more important because of its tendency to be repeated.

Responding to Nunberg's observation that a heated discourse about respectful expression has been taking place for more than a decade already, Denby protested, "I'm not calling for niceness, or saying we should all curl up into one another's laps. But we could, as the president says, respect each other enough to differ without trying to annihilate each other, because now we're in a very difficult situation in which we have to pull together."

Still, said Denby, who acknowledges in his book that he's a fan of "nasty comedy, incessant profanity, trash talk, any kind of satire, and certain kinds of invective," some subjects simply cry out for snark: "Dick Cheney shooting his best friend in the puss, Eliot Spitzer sleeping with the women he's been prosecuting, and over-rated expensive restaurants." What's more, he said, "You wouldn't want to know anyone who wouldn't want to make fun of the movie Australia," adding, "some of us get paid to do that."