'Understanding Science' website clarifies what science is and is not

It is: dynamic and creative, 'iterative and messy.' It is not: boring

| 05 February 2009

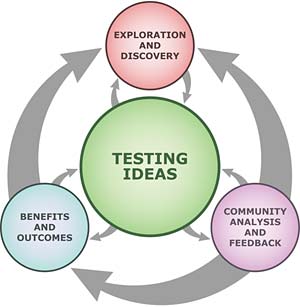

A flowchart on the Understanding Science website represents the process of scientific inquiry. Most ideas take a circuitous path through the process, shaped by unique people and events.

A flowchart on the Understanding Science website represents the process of scientific inquiry. Most ideas take a circuitous path through the process, shaped by unique people and events. BERKELEY — If you think you know what science is and how science works, think again.

A new Berkeley website called Understanding Science paints an entirely new picture of what science is and how science is done, showing it to be a dynamic and creative process rather than the linear — and frequently boring — process depicted in most textbooks.

Funded by the National Science Foundation as a resource for teachers and the public, the material was vetted by historians and philosophers of science as well as by K-12 teachers and scientists from many disciplines.

“Through this collaborative project, we hope to overturn the paradigm of how science is presented in our classrooms,” says Roy Caldwell, a Berkeley professor of integrative biology who led the project along with colleague David Lindberg. “The website presents not the rigid scientific method but how science really works, including its creative and often unpredictable nature, which is more engaging to students and far less intimidating to those teachers who are less secure in their science.”

“Part of the fun of science is lost when you present it as a linear thing,” says Natalie Kuldell, an instructor in biological engineering at MIT and one of 18 scientific advisers for the project. While the five-step process described in textbooks — ask a question, form a hypothesis, conduct an experiment, collect data, and draw a conclusion — isn’t wrong, “it is an oversimplification,” she says.

The core idea, says Judy Scotchmoor, assistant director of the UC Museum of Paleontology at Berkeley and coordinator of Understanding Science, is that science is about exploring, asking questions, and testing ideas. The site provides a Science Checklist that can be used to determine just how “scientific” particular activities are.

“The goal was to present the concept that testable ideas are right at the center of science, and if you don’t generate testable ideas, then you are really not doing science,” Kuldell says.

Testing, however, is intertwined with exploration and discovery (the “cowboy” aspect of science, in the words of one project adviser), the review of hypotheses and theories by skeptical peers, and actual application of the science to real-world problems.

Within the website, personal stories contributed by top scientists around the country illustrate the interplay of exploration, peer review, and outcomes, and demonstrate the different pathways to discovery taken in different fields of science, from biology to cosmology.

Scotchmoor hopes that the site will show students and the public that “science really is an adventure. There are certain rules that you need to follow, but really you can’t predict where questions will take you.”

Following the site’s debut on Jan. 5, during the launch of Year of Science 2009, it received rave reviews from New York Times science writer Carl Zimmer, who referred to it in his blog as “a guided tour through the basic questions of what science is and how it works.”

Four years ago, Scotchmoor, Caldwell, and Lindberg created a website called Understanding Evolution that now provides a much-needed resource for teachers and the public.

“We discovered, however, that there was a lot of confusion about what science is and isn’t,” Scotchmoor says. “We found nothing on the Web that would clarify this, so we approached the National Science Foundation to create this unique K-16 site.”

“We discovered, however, that there was a lot of confusion about what science is and isn’t,” Scotchmoor says. “We found nothing on the Web that would clarify this, so we approached the National Science Foundation to create this unique K-16 site.”

“Teachers had misconceptions, such as what a theory is or whether creationism is science,” Caldwell says. “Many even thought science wasn’t creative, in part because of cookbook labs, in part because of the emphasis on testing factual knowledge, not process.”

With advice and input from historians, philosophers, teachers, and scientists, Scotchmoor, Caldwell, and Lindberg constructed Understanding Science from scratch, modeling it after Understanding Evolution. The new site has been endorsed by the California Science Teachers Association and the American Institute of Biological Sciences, and will be part of the next edition of a popular high-school biology textbook, Biology (Prentice Hall), by Ken Miller and Joe Levine.

Kuldell uses the site in her second- and third-year college lab courses to “set the expectations of my students, [to show them] that science is iterative and messy and doesn’t always make a clean story — and that that should be expected. You work and then you rework, you get feedback, you rethink your ideas, and then retest. Science isn’t quite as neat as people wish it were and think it should be.”

The site will continue to grow, with personal profiles of scientists and their research, each accompanied by a flow chart showing how they proceeded from ideas to discovery.

“We hope these cool stories will draw people in,” Scotchmoor says.