What's cooking at the Library?

The Koshland bioscience library's culinary collection provides food for thought for local chefs, campus researchers, and home cooks

| 12 February 2009

BERKELEY — Dishes like pig’s-ear salad and long-roasted lamb neck now appearing on fashionable San Francisco restaurant menus — from chefs embracing the “whole animal” concept of putting all precious bits to good use — might seem cutting-edge, even daring.

Spooning the stacks: The Koshland Library's Norma Kobzina oversees the culinary collection there. (Peg Skorpinski photo)

Spooning the stacks: The Koshland Library's Norma Kobzina oversees the culinary collection there. (Peg Skorpinski photo)But a quick trip through the varied assortment of books on food, food science, and cooking housed in the campus’s Marian Koshland Bioscience and Natural Resources Library gives the lie to that notion, as a glance at a volume of daily menus from San Francisco’s Occidental Hotel, circa 1880, makes clear.

Everyday entrees served at the esteemed Montgomery Street hostelry included “calf’s head poelé,” “baked brains,” and “lamb’s heart sauté” — dishes not likely to make a comeback, even on the edgiest San Francisco tables, anytime soon.

The Occidental didn’t survive the 1906 earthquake and fire. But its early menus did, republished in one of the 1,500 eclectic books that make up the Holl Collection, the juicy heart of the bioscience library’s holdings of some 5,000 cookery and food-related volumes.

The books were collected by George Holl, a San Francisco painter who was Fox Theatres’ West Coast art director during the first half of the 20th century and, in the words of the legendary San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen, “San Francisco’s No. 1 gourmet and connoisseur.” Four years after Holl’s death in 1946, his brother Walter turned the books over to Berkeley, where they were initially shelved as part of the agriculture collection in the Main Library. The collection moved to Giannini Hall in the early 1960s, and then in 1995 relocated once more, to the Valley Life Sciences Building as part of the then-new bioscience library.

Chefs and scholars alike

Apart from the Holl books, the library’s holdings include early books on nutrition, diet, and health, overviews of the foods of various cultures, the amusing and literate writings of culinary documentarians like Waverley Root, traces of early and modern California cuisine, and many, many cookbooks.

A collection this varied is bound to be used for many purposes. Environmental-science students use the books to analyze such issues as the effects on the land of growing and processing food. Dietetics students use them to track dietary patterns or changes among populations: how much fat is consumed by various cultures, or points of comparison between the eating habits of Asians and Asian Americans. Natural-resources librarian Norma Kobzina, in fact, teaches classes every semester in the use of the cookery books as scientific references.

The collection is a resource for local chefs as well, professional and otherwise. Paul Bertolli, now producing artisanal salumi in Berkeley under the Fra’ Mani label, used the collection to plan Escoffier dinners at Chez Panisse when he cooked there; he once enlisted Kobzina to research the kind of wood originally used for olive-oil barrels, she recalls. But any aspiring cook with a Cal ID who wants to learn the culinary tricks of local luminaries like Boulevard’s Nancy Oakes or Chez Panisse’s Alice Waters can check out their cookbooks and take them home to inspire experiments on friends and family.

“There’s greater use of [the books] now,” Kobzina says, partly because of publicity about the collection and partly because some of the books have been digitized by Google and Yahoo and people are stumbling across them online.

These books can’t stand the heat

The Holl Collection is the library’s piéce de resistance, and its books go nowhere near a stove. They’re kept under lock and key and can be viewed only by request, for use at a single table watched by the reference librarian with the kind of attention normally paid a Hollandaise about to curdle.

Though Holl was from San Francisco, his collection is far from parochial, containing books on cooking and culture from every continent except Antarctica, starting with recipes from Imperial Rome (in Latin) to 1930s Africa to London’s Chinatown circa 1932, and on to Scotland, Russia, and many books from Germany. He also had an eye for American cooking, with selections ranging from the foodways of Martha Washington and a wealth of Southern cookbooks to celebrity “cookbooks” featuring such gems as recipes for Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Eggs President (scrambled, basically) and Robert Frost’s take on a baked potato (cooked outdoors in wood ashes, the only thing the poet says he ever cooked).

The oldest book, bound in burnished mahogany leather and lettered in gold, dates back to 1643, its pages so brittle they crinkle audibly when turned. The Italian tome republishes Renaissance chef Bartolomeo Scappi’s Opera dell’arte del Cucinare, a compendium of recipes for “pizze” and other dishes that Scappi concocted for popes and cardinals during the early 1500s.

Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, who tied a nation's destiny to its food.

Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, who tied a nation's destiny to its food. At the collection’s core are the early (if mostly not first) editions of a virtual who’s who of French cuisine from the 17th to 20th centuries, among them Auguste Escoffier, Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, Antonin Carême, Prosper Montagne, and the lively literary gourmand who went by the pen name Curnonsky (a moniker read by his fellow citizens as "Whynot-sky").

For example, a 1926 volume marking the centennial of Brillat-Savarin’s death, De la Gastronomie suivie d’Histoires Gastronomiques, delivers (in French) many of the jowly 18th-century jurist and gourmand’s bon mots about food, as immortalized in his 1826 Physiologie du goût (better known in English as The Physiology of Taste). Chew on this: “Animals feed themselves; man eats; the soulful man, only, knows how to eat.” Or this: “The destiny of nations depends on the manner by which they feed themselves.”

In the same volume, Brillat-Savarin tells delightful stories that prefigure the work of the 20th century’s M.F.K. Fisher, including “The Anecdote of the Oysters,” in which a friend sits down to sate himself with oysters but, sadly, fails when the experiment is halted after his 32nd mollusk, the kitchen staff exhausted.

From a more recent era, the gastronomic writings and travelogues of Curnonsky, as the early 20th-century French writer Maurice Edmond Sailland called himself, provide a vivid lesson in the genre of restaurant reviewing. (Yelp contributors, take note.) Among the translated works in the collection is the first book of Curnonsky’s département-by-département multi-volume Epicure’s Guide to France, a 1926 paean to the delights of Normandy — a tour that draws the seasoned gourmand's admission that “notwithstanding our zeal and capacity, we cannot eat more than four or five meals a day.”

In his introduction to that volume, Curnonsky writes as only a Frenchman can: “We have eaten all kinds of cooking, from the admirable and learned Chinese cooking to the dreadful thermo-chemical and doctored food served in the American Palace Hotels … , which brought us … to the conclusion that one can be fed anywhere, but that one really eats in France only.”

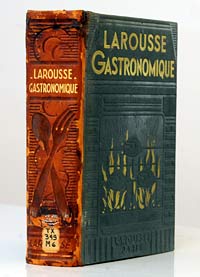

Prosper Montagne's encyclopedic Larouse Gastronomique, a compendium well-deserving of the sobriquet "bible of French cuisine." (Peg Skorpinski photo)

Prosper Montagne's encyclopedic Larouse Gastronomique, a compendium well-deserving of the sobriquet "bible of French cuisine." (Peg Skorpinski photo)Another Gallic standout is a first edition of the modern bible of French cuisine, Montagne’s Larousse Gastronomique, published in 1938 with a preface by Escoffier and gold flames licking embossed spit-roasting chickens on its dark-green cover.

Inside, its simple A-to-Z format contains the entire world of French cuisine, including six pages on butter. Even a cursory read makes one thing obvious: Little that appears on trendy 21st-century menus, from cardoons to beef cheeks, is actually new (except maybe for foams and other forms of so-called molecular gastronomy).

California, here we cook

Another culinary path through the collection may be followed by those who would trace the genesis of “California cuisine” — though the Holl Collection ends around the time that style’s alleged founder, Alice Waters, was born.

A good point of departure is Ana Bégué Packman’s Early California Hospitality from 1938, which starts with the pine nuts, wild greens, and grapes of the native people before documenting the staples introduced by the Spanish from Mexico: corn, tomatoes, chiles, brown sugar. (Wheat tortillas, it turns out, were an adaptation by the Spanish to Southern California’s dry climate, which grew wheat better than corn, Packman writes.)

So much for our roots. By the 1880s, “California poached eggs” meant eggs slathered with a tomatoey white sauce. English cooking has nearly conquered the culinary landscape, according to the California Practical Cook Book, published in Oakland, which in addition to a multitude of cake recipes incorporated formulas for making various kinds of yeast and fashioning toothpaste from charcoal and honey.

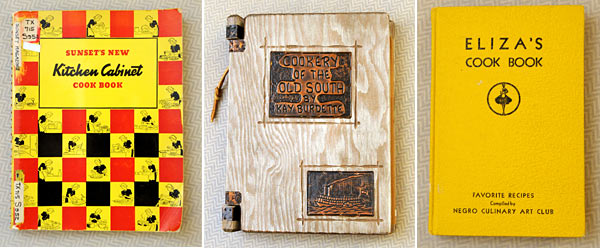

By 1938, California cuisine (though no one called it that yet) had evolved into the hamburger pinwheels, Stinson Beach baked ham (cooked with apples and grape juice, yielding a grape-juice gravy), and multiple Jell-O-ring salads of Sunset magazine’s New Kitchen Cabinet Cook Book. Tamale pie was a popular pan-ethnic recipe, turning up in the pages of many books, from Eliza’s Cook Book, compiled by the Negro Culinary Art Club of Los Angeles in 1936, to Soup to Nuts, a 1937 recipe collection from San Francisco’s Congregation Emanu-El Sisterhood.

Bringing the California-cuisine theme to the present requires a trip back to the open stacks, where many books offer the modern-day version of the impeccably sourced, ingredient-driven cooking generally credited to Alice Waters at Chez Panisse. Waters’ own papers, however, reside in the Bancroft Library.

California cuisine is just one example of the kinds of culinary, literary, and scientific journeys offered by the Koshland Library's cookery books, which provide insight into both the highly contemporary and the thoroughly antiquarian, while serving as a resource for both the chef and the scholar.