Home away from home for many at Berkeley, Stiles Hall's living room comfortably holds a crowd. Here, from left to right, Jennifer Church, office manager; George Austin, transfer-students-program director; Dave Stark, Stiles director (holding a photo of the original Stiles); Everardo Mora, transfer-program coordinator; Jonathan Brack, a director of Berkeley Scholars to CaI; and Folasade Scott, transfer-program coordinator. (Peg Skorpinski photo)

Home away from home for many at Berkeley, Stiles Hall's living room comfortably holds a crowd. Here, from left to right, Jennifer Church, office manager; George Austin, transfer-students-program director; Dave Stark, Stiles director (holding a photo of the original Stiles); Everardo Mora, transfer-program coordinator; Jonathan Brack, a director of Berkeley Scholars to CaI; and Folasade Scott, transfer-program coordinator. (Peg Skorpinski photo)Stiles Hall: a 'living room' with a committed fan club

A legendary incubator of community programs — and activists — celebrates 125 years of off-campus vitality

| 04 March 2009

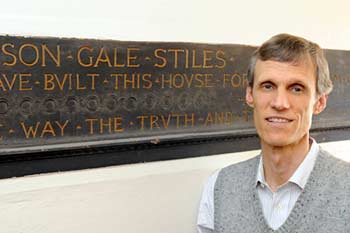

Director Dave Stark keeps Stiles true to its mission, carved into a long dedication stone that is the sole remaining piece of the nonprofit's original building. It is embedded in a wall of an upstairs hallway in the current Stiles, which was built in 1951.

(Peg Skorpinski photo)

Director Dave Stark keeps Stiles true to its mission, carved into a long dedication stone that is the sole remaining piece of the nonprofit's original building. It is embedded in a wall of an upstairs hallway in the current Stiles, which was built in 1951.

(Peg Skorpinski photo)BERKELEY — Just last month, $750,000 fell into Stiles Hall’s lap from out of nowhere, a bequest from an alum named Theodore Judge, class of ’42, whose history with Stiles is unremembered and unrecorded 67 years later.

Clearly, Stiles left its mark on Judge. His gift is a tangible expression of the kind of loyalty that the off-campus, nonprofit, social service center has generated in Berkeley students, faculty, and staff since its inception in 1892 in an imposing red brick Romanesque Revival home that stood where Haas Pavilion is now.

Housed today in a modest two-story building on Bancroft Way across from campus, Stiles continues to play the same unique and vital role in Berkeley life that it has for 125 years — as a mix of student-services center, cauldron of social causes, incubator for campus and community initiatives, and an important contributor to diversity on campus.

Now as ever, Stiles inspires a steady stream of campus types to cross Bancroft to take part in its many community-outreach projects, to mentor educationally disadvantaged schoolkids who might otherwise never get to college, or simply to find a safe space to talk freely about sensitive issues away from campus.

In honor of Stiles’ 125th anniversary, a celebration is planned for 4 p.m., Saturday, March 14, at Alumni House.

Among those present will be many of the Stiles faithful, including federal Judge Thelton Henderson ’55, J.D. ’62, who has been involved in Stiles since he arrived at Berkeley in the early 1950s. Despite a jam-packed schedule that finds him currently overseeing the sprawling court case over medical care in California’s prisons, Henderson still finds time to invite Stiles-involved students to his office for sandwiches and some free advice on becoming lawyers.

“For me, this kid out of south-central L.A. who wasn’t sure where he belonged at Cal, Stiles gave me a sense of belonging. I felt at home there. It was critical to my getting through that period and becoming who I am,” says Henderson, who serves on Stiles’ board.

Emblematic of Stiles’ value to both the campus and the community, Chancellor Robert Birgeneau and the city of Berkeley’s first family, Mayor Tom Bates and state Sen. Loni Hancock, will also be on hand at the March 14 event to fete Stiles’ enduring commitment to multiculturalism, freedom of speech, helping those who need it, and standing up for the underdog.

“It’s been known as a place that brings different communities together and focuses on multiculturalism of all kinds — race, class, sexual orientation, and other. It engages the university in the community, and brings the community into the university,” says Steve Lustig, Berkeley’s associate vice chancellor for health and human services, who volunteered as a Stiles mentor 42 years ago and serves on its board.

A red brick Romanesque Revival mansion built in 1892, the original Stiles Hall stood on the bank of Strawberry Creek, where Haas Pavilion is today, and housed the Y.M.C.A.

A red brick Romanesque Revival mansion built in 1892, the original Stiles Hall stood on the bank of Strawberry Creek, where Haas Pavilion is today, and housed the Y.M.C.A.The first Stiles Hall housed the YMCA and took its name from Anson G. Stiles, whose widow, Ann Stiles, donated the building. In 1932, Stiles Hall moved to a small Victorian where Lower Sproul Plaza now sits. As the campus absorbed surrounding blocks, Stiles moved to its current building at the corner of Dana and Bancroft in 1951 and eventually separated its activities from the Y.

From early on, Stiles opened its doors to controversial speakers not then allowed on campus, including American Communist Party leader Gus Hall in 1962.

Dave Stark, executive director for the last 12 years, likes to tell the story of the African American man in his 60s who wandered into Stiles a few years back, found his way to the upstairs community room and said aloud, in wonder, to no one in particular: “This is it! This is it!”

Stark overheard him and asked, “It’s what?”

“This is where Malcolm X spoke. I was here,” the man responded. The civil-rights leader had spoken there in the early 1960s, before the Free Speech Movement opened up the campus to speakers of all political bents.

Changing times, unchanging mission

Stiles’ mission of community service remained unchanged over the years, while the issues it has taken up have changed with the times.

During World War II, Stiles volunteers helped Japanese Americans threatened with detention in internment camps. As early as the 1950s, the hall served as a gathering place for educators concerned about diversity in the Berkeley and Oakland schools. During the 1960s, free speech and civil rights were at the fore.

“Having a very small number of African American students and faculty on campus” is a current focus, says Stark. Stiles’ community programs take direct aim at the problem in ways that the campus cannot since the passage of Proposition 209 in 1996.

Volunteers in its Berkeley Scholars to Cal program give 75 black and Latino students academic and social support from fifth through 12th grade, and the results so far are promising: almost a third of the students have 4.0 GPAs, and three-quarters have a B average or better, according to early studies. The first cohort in the program, which started in 2001, is in high school now.

Stiles’ Experience Berkeley brings underrepresented high- school and community-college students to Berkeley to get to know the campus, and has increased the number of them who enter as freshmen or transfers. Its mentoring program matches 250 volunteers a year with schoolkids, a program that past mentors say gives as much to the volunteers as it does to their young charges.

Irene Hegarty, now Berkeley’s director of community relations, was a Stiles tutor in the Oakland schools during the late 1960s and says the experience “was an education in itself.” It opened her eyes to the realities of inner-city schools and, indirectly, brought her back to Berkeley in her current job — where she works with Stiles again.

Innumerable campus and community services have started as independent activities at Stiles and then taken hold in the university or community. The first student services, freshman orientation, international student advising, the housing coops, and the Bridges Multicultural Resource Center all were hatched at Stiles, according to Stark.

A Stiles program that helped poor people who were arrested improve their chances of getting out of jail on their own recognizance, launched in the early 1960s, has been incorporated into the Alameda County court system. The Options Recovery Service, another Stiles hatchling that helps people break the drugs/jail cycle, now operates on its own in Oakland, Stark says.

Less well known is Stiles’ role as a support for Berkeley faculty, staff, and students, he adds. Besides the enrichment provided by volunteering and mentoring, Stiles Hall has long served as an informal “living room” for faculty of color, according to Gibor Basri, Berkeley’s vice chancellor for equity and inclusion, who will be at the 125th anniversary event.

Informal get-togethers organized by Stark several times a year offer a place “where we can come and chat about issues away from any formal campus structure,” Basri says. “These meetings have allowed folks to meet each other regardless of discipline, and germinated ideas that have later borne fruit in advancing issues of faculty equity and increasing inclusiveness.”

Berkeley’s Black Graduate Student Association came into being in 2004 after Stark invited a group over for sandwiches, and they “were so encouraged to see each other because their number is very small on campus.” Now, the association supports new students and does community work and outreach.

All of these efforts have helped boost Berkeley’s diversity profile, from top to bottom, Stark says. Chancellor Birgeneau, he adds, has been very supportive and has encouraged corporations to fund Stiles’ projects, he adds.

Stiles’ role remains as it’s ever been, for 125 years: To listen to students, faculty, or staff who feel something is missing on campus — and to provide a space for them, maybe lunch, and then get out of the way.