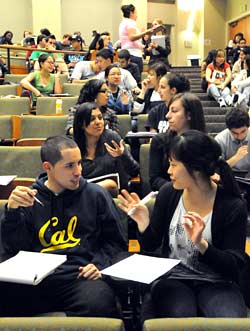

Ingrid Seyer-Ochi's students (above) grapple with difficult topics. "Even in large-enrollment classes," says the assistant professor of education, "we can work to make these conversations happen." (Peg Skorpinski photo)

Ingrid Seyer-Ochi's students (above) grapple with difficult topics. "Even in large-enrollment classes," says the assistant professor of education, "we can work to make these conversations happen." (Peg Skorpinski photo)American Cultures: Discussing differences, building bridges

Berkeley's unique undergraduate requirement helps students learn about race, culture, and ethnicity

| 09 April 2009

| 20 years of AC |

A public forum, "American Cultures: From Concept to Classroom (1989-2009 and Beyond)," will take place Thursday, April 16, from 5 to 7 p.m. at the Free Speech Movement Café at Moffitt Library. Panelists will be Mark Brilliant, professor of history and American studies; Waldo Martin, professor of history; Ingrid Seyer-Ochi, assistant professor, Graduate School of Education; and moderator Bill Simmons, the first director of the American Cultures Center. An American Cultures exhibit that shares the name of the forum is on view at Moffitt Library through June 30. For information about the American Cultures Center (including guidelines for creating an AC course), visit american |

BERKELEY — "Race is very hard to talk about, and unfortunately, people rarely discuss it with others different from themselves," says Assistant Professor of Education Ingrid Seyer-Ochi. She has made it a goal to get her undergrads engaged in tough conversations about race, the kind that push buttons, demand openness and vulnerability, and offer new ways of seeing the world.

"We have this vision of what we think diversity on this campus should be, and it's my sense that students aren't engaging with each other across lines of race, class, and difference that often at all," says Seyer-Ochi. In a course titled Experiencing Education: Diversity and (In)Equality In and Beyond Schools, Seyer-Ochi has introduced an exercise she calls "difficult dialogues," in which students entertain alternative perspectives so that they might "rethink attitudes, assumptions, and political and social understandings."

(Left to right) Ingrid Seyer-Ochi and Victoria Robinson (Wendy Edelstein photo)

(Left to right) Ingrid Seyer-Ochi and Victoria Robinson (Wendy Edelstein photo)That course is one of many that, in addition to their other virtues, satisfy the campus's American Cultures (AC) requirement, which was developed in response to late-1980s pressures to address issues of race and ethnicity at Berkeley. Courses that satisfy that requirement provide an unusual opportunity to bridge divides and examine beliefs. As stipulated by Academic Senate guidelines, they must focus on at least three of five groups — indigenous peoples of the United States, African Americans, Asian Americans, Chicano/Latino Americans, and European Americans — by employing a theoretical and analytical approach to race, culture, and ethnicity while also exploring the groups' role within or in relation to the United States. A Senate subcommittee, which Seyer-Ochi chairs, reviews course proposals and determines whether they meet the intent of the guidelines.

All undergraduates must take — and pass — an AC course in order to graduate. The options range widely: AC courses are offered by 64 departments in the College of Letters and Science as well as in many unexpected disciplines across campus, including engineering, integrative biology, architecture, agriculture and resource economics, and environmental science, policy, and management.

Students meeting their American Cultures requirement are participating in what one emeritus professor calls "one of the most important curricululm-reform

projects in the history of this campus."

(Peg Skorpinski photo)

Students meeting their American Cultures requirement are participating in what one emeritus professor calls "one of the most important curricululm-reform

projects in the history of this campus."

(Peg Skorpinski photo)Students in AC classes come from different majors and possess varying degrees of knowledge of race, making the AC classroom a "unique educational space" on the Berkeley campus, says Victoria Robinson, coordinator for the American Cultures Center. "AC teaches civic skills. It's a lived experience. It's not just about the intellectual content — it's very much about dialogue," she says.

Bill Simmons, a professor emeritus of anthropology who was the American Cultures Center's first director, recalls the late-'80s days of student foment that led to its creation, during an era when Berkeley and many campuses across the nation were shifting demographically. These students, he says, were "Americans sitting in the classroom who nevertheless felt left out of entire disciplines."

Simmons chaired the Academic Senate Committee on Education and Ethnicity that was established to respond to the student unrest. Although students demanded an ethnic-studies requirement, Simmons says, the committee sensed that "there was something deeper than that going on. The issue became, 'We're Americans too. Where do we fit into these traditional fields that attempt to understand the American experience?'"

Simmons notes that when the committee decided that AC courses would use a comparative approach and examine a minimum of three groups, they discovered that no such courses then existed, not even in the Department of Ethnic Studies. A summer institute helped faculty develop courses that would fulfill the new requirement, and after three years, 200 AC courses had been created. ("Faculty wanted to do this," says Simmons.)

Ling-chi Wang, emeritus professor of Asian American studies and one of the founders of Berkeley's ethnic-studies department, served on the AC committee with Simmons. He calls the AC requirement "one of the most important curriculum-reform projects in the history of this campus. American Cultures challenges each discipline to raise questions that they had never raised before, and in the process, they have uncovered unknown aspects of their own disciplines."

Changing with the times

The boundaries of the AC re-quirement have expanded, which has allowed new AC courses to reflect recent scholarship, says Robinson. For example, she notes, "you can now make an international comparison of what it means to be Chinese globally by relating the Chinese American experience to cross-border movements," such as those in Taiwan. "That kind of elasticity wasn't read into the requirement 20 years ago. It is today," she says.

More evidence that the requirement has matured: Racial ethnic groups are no longer viewed as monolithic entities, such as African American and Asian American. Once those pan-ethnic organized groups initially were the de facto foundation of an AC course, says Robinson. Now AC's guidelines include sub-groups and sub-classifications, she says, "so you could focus on Korean Americans in comparison with El Salvadorans."

Large-enrollment AC courses are fewer, while there are more upper-division courses with enrollments of 25 to 70 students. "This makes me think that the students and/or the faculty are demanding more intimate, academically mature environments to discuss American Cultures material," says Robinson. "You could also explain it by the fact that we're 20 years into a critique of multiculturalism, and that the students are far more sophisticated in their self-identification of what race and culture means to them."

The American Cultures Center is also directing its efforts outward by partnering with Cal Corps on the Berkeley Engaged Scholarship Initiative, a campuswide program that supports faculty who develop community-based components for new or existing courses (see berkeley.edu/news/berkeleyan/ 2008/10/09_program.shtml).

With Chancellor Birgeneau's commitment to diversity, as em-bod-ied by the establishment of the Division of Equity and Inclusion, the conversation about race will continue into the foreseeable future at Berkeley.

Seyer-Ochi, who was awarded the campus's first American Cultures Innovations in Teaching Award last spring, observes students coming out of her class with a changed understanding of themselves and of race in this country. "I never teach that we are these racial categories. They are social constructions that are very powerful that we can't completely disrupt, yet there are all sorts of opportunities for us to think and learn about how race functions and to see ways to challenge that process to make a less inequitable world."