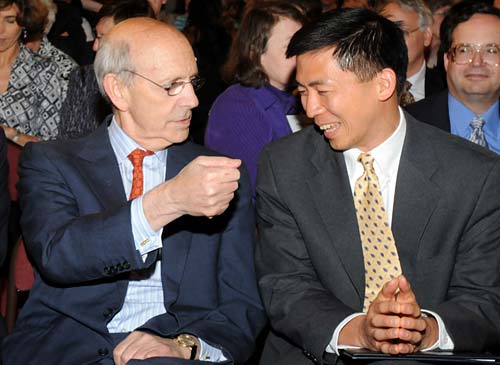

Jusice Breyer (left) in an informal exchange with law professor Goodwin Liu, a noted constitutional scholar. (Peg Skorpinki photo)

Jusice Breyer (left) in an informal exchange with law professor Goodwin Liu, a noted constitutional scholar. (Peg Skorpinki photo)Breyer: Faith in reason, or faith in force?

Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, in a campus talk, describes the law as a 'tapestry' held together by citizens' willingness to keep it from unraveling

| 16 April 2009

BERKELEY — U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, one of the world's most powerful jurists, issued a modest plea for justice and reason at International House last week, portraying the rule of law as "a subtle thing" that depends upon the willingness of citizens to follow it — and the determination of governments to enforce it.

Law "is not God-given," he affirmed, nor is it "a sure thing" that even the decrees of the highest court in the land will ever be implemented. Here in the United States, "the most you can say, or hope to say, is that the tendency to follow the law has helped."

The San Francisco native (and Stanford grad), speaking Friday at the invitation of the Blum Center for Developing Economies, all but apologized for "my narrow parochial view" as a jurist, and for lacking expertise in poverty and development policy. "Even though you are not lawyers, you would invite a lawyer and a judge to come speak to you," he told his appreciative, frequently charmed audience. "That's broad-minded, and I thank you."

Breyer, appointed to the Supreme Court in 1994 by President Bill Clinton, is generally regarded as moderate-to-liberal. Discussing his book Active Liberty in 2005, he explained the title by telling NPR that "democracy works if — and only if — the average citizen participates."

In the first of two campus appearances — he was scheduled to preside over a moot court at the law school this Tuesday — Breyer cited the efforts of nine African American students to take their places at Little Rock Central High School in 1957, three years after the high court's landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education. Despite the desegregation ruling, Arkansas Gov. Orville Faubus deployed the National Guard to block the students from entering the building.

U.S. Supremem Court Justice Stephen Breyer (Peg Skorpinski photo)

U.S. Supremem Court Justice Stephen Breyer (Peg Skorpinski photo)

"We had nine justices" who signed the unanimous Brown decision, noted Breyer. "But they didn't have the militia. It was Governor Faubus who had the militia."

It took President Dwight Eisenhower, he added, to send in the army's 101st Airborne Division to enforce the court's ruling. "That," said Breyer, "was a great day for the rule of law."

"Some progress has been made" over the course of U.S. history, he observed. In the 19th century, for example, the Supreme Court ruled that the Cherokee Nation had a constitutional right to remain in Georgia. But President Andrew Jackson, siding with white settlers who coveted Indian land, said, "Let's see them enforce it."

By contrast, the court's decision in Bush v. Gore — which upheld Florida's awarding of its electoral votes to George W. Bush in 2000, thereby sending him to the White House — was implemented with "no riots," and without the need for the kinds of extraordinary action called for in hotly disputed cases of times past.

The point, Breyer made clear, was not that the decision was correct, but that it was adhered to, however unsatisfying the result. "Hey, I didn't like Bush v. Gore. I dissented. All right?" he quickly added, drawing the biggest applause of the afternoon.

Amiable hopscotching

Describing the law as "a tapestry" that "unweaves at night," Breyer attempted to sketch what he called "the obvious links between law and development." His 30-minute talk — which was followed by an onstage conversation with Goodwin Liu, associate dean of the law school, and Blum Center founder (and UC Board of Regents chair) Richard Blum — hopscotched amiably from musings on the nature of law and justice to recountings of brushes with the likes of Alan Greenspan, Sen. Ted Kennedy, and President Barack Obama.

Greenspan, the former Federal Reserve chairman, was asked once if there was one thing that makes a difference in a country's development, Breyer remembered. His answer: "whether there was … a rule of law."

In order to have economic development, Breyer explained, a nation needs investment. That, in turn, depends on a sense of security, which hinges on fairness. But "independent justice," he added, is a relatively unknown quantity in much of the world.

He recalled a conversation he had in Ghana with a high-ranking jurist who wondered what was meant by the concept of "judicial independence," and a meeting in Moscow at which Boris Yeltsin, then the Russian president, addressed an assembly of judges. It was there Breyer learned about "telephone justice," in which — as one attendee explained to him — "a party boss calls you and tells you how to rule."

Nonetheless, Breyer — sounding at times like the juidicary's answer to columnist Thomas Friedman, author of The World Is Flat — invoked the increasingly "horizontal" nature of the global community as a sign that the delicate tapestry of the law is gaining strength worldwide.

"The most important division in today's world," he said, is between those countries that put their "faith in reason" and working together to resolve problems, and "those who have lost that faith, and believe in nothing but force." Just as it did in the United States, he cautioned, "it takes time" to build "habits" of independent justice. But the growing integration of autonomous nations, he suggested, increasingly demands that they strive to work things out via mutually agreed-upon legal frameworks, such as international organizations and treaties.

Systems in harmony

"The law today in the United States is not exclusively American law," said Breyer, noting that he and his high-court colleagues have a handful of international cases on their docket, and regularly hear briefs from foreign countries. Similarly, the establishment of the European Union has prompted a "harmonizing" of its member nations' legal systems, while South Africa has "picked things from around the world they thought would work in their constitution."

Drawing a link with U.S. history from Andrew Jackson to Bush v. Gore, though, he added — in answer to a question from Liu — that while "an independent judiciary is a help" in pushing societies toward law and reason, there are "no guarantees."

Despite the well-known ideological differences among his court colleagues, Breyer said he had "never heard a voice raised in anger," nor witnessed any rudeness. "That's the way it was my first day on the court, and that's the way it still is."

Asked about the impact of potential new Supreme Court appointees during Obama's presidency, he quoted former justice Byron White, who said, "With every new appointment, it's a new court." Breyer concurred, promising "dynamic changes with new people."

And he lamented the 2006 retirement of Sandra Day O'Connor, which left Ruth Bader Ginsburg the lone woman on the nine-person bench.

"The truth is, I think it was better to have more women," Breyer said. "[But] if you say, 'Why was it better?' I have to say I don't know."