Philip Brett Fund to support LGBT studies

New graduate fellowship for research in any field honors groundbreaking music professor

| 11 June 2009

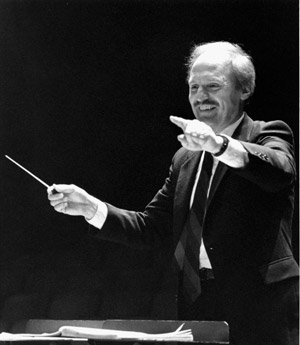

Philip

Brett (Kathleen Karn photo)

Philip

Brett (Kathleen Karn photo)BERKELEY — Philip Brett, an eminent music scholar at Berkeley for 24 years, set academic ears to ringing in 1976 with the mention of a single word in a lecture on composer Benjamin Britten. The word was homosexual.

Calling it "pornography," several scholars walked out of the lecture, delivered at a national meeting of the American Musicological Society, recounts Davitt Moroney, a graduate student under Brett at the time and now a Berkeley music professor himself.

But Brett's work on the relationship between Britten's gayness and his music, which he later developed into his pioneering and still-discussed paper "Britten and Grimes," was serious. And in that lecture, he initiated the entire field of LGBT — lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender — musical scholarship, Moroney says.

Now, 33 years later — and seven years after Brett's death — hundreds of scholars are working in the field, Moroney notes. And thanks to the efforts of Moroney and others, Berkeley has just launched the Philip Brett LGBT Fund, the campus's first fellowship endowment designed to support LGBT-related research by graduate students studying in any field.

Set up just two months ago, and announced recently on the website of Berkeley's main LGBT staff and faculty network, LavenderCal, the Philip Brett LGBT Fund already has drawn in more than $10,000 in gifts — the level required to qualify for matching funds from the Chancellor's Challenge for Student Support, according to Sharon Page-Medrich, an academic analyst in the Graduate Division and, along with Moroney, a key person in the effort to get the fund going.

Contributions are arriving steadily from staff, faculty, undergraduates, and graduate students, and their partners, both LGBT and not, Page-Medrich says. Moroney adds that he's delighted that such a fund has started entirely as a grassroots effort.

"Stipends and fellowships are crucial to students' research," says Andrew Szeri, dean of the Graduate Division. "This unique fund will enable our graduate students to pursue LGBT-related scholarship in any field of their choice. Visionary members of our faculty and staff banded together to launch this initiative. Now all friends of the campus, including alumni, can add their own investment to help Berkeley's students impact both the academy and the world."

Berkeley currently offers an undergraduate minor in LGBT studies and a graduate-level designated emphasis in women, gender, and sexuality. Earlier this spring, the campus hosted "Queer Bonds," an interdisciplinary conference that brought in scholars from all over the world to explore aspects of emerging LGBT scholarship in a variety of fields. Elsewhere among the academic elite, Harvard announced just last week that it will be endowing a chair in LGBT studies.

"Nationally and internationally, LGBT-related studies have achieved an intellectual critical mass that makes the legitimacy of such inquiries much harder to challenge," says Page-Medrich. "The fruitfulness and creativity of the scholarship is very exciting. It opens up new ways of looking and seeing and noticing."

Out of the closet early on

Berkeley's new fund honors a professor who was not only a groundbreaking scholar but an inspiring teacher, Moroney wrote in an obituary of his mentor, colleague, and friend.

British-born and Cambridge-educated, Brett landed at Berkeley in 1966 and found it liberating. He met his life partner, George Haggerty, now an English professor at UC Riverside, and they lived together for 28 years until Brett's death, the day before his 65th birthday.

Brett became one of the few faculty to come out of the closet at Berkeley in the 1970s, according to Moroney's account.

Brett was an expert in Eliza-bethan music, especially that of the 16th-century composer William Byrd, who had been oppressed as a Catholic in Anglican England. Following a similar thread, Brett started delving into the oppression suffered by Britten as a homosexual man in 20th-century England, at a time when gayness was a criminal offense carrying a long prison sentence.

His research tracing this theme in Britten's opera Peter Grimes became the subject of his famous 1976 lecture and subsequent paper. According to Moroney, they represented the first time an openly gay musicologist had discussed in public a gay subject in such a scholarly context.

"At the time it was a courageous act, and it opened the door for many others who had been hesitating to take such a public step," Moroney wrote. "It gave many of us the courage to come out in the 1970s, when it was not easy." He adds that for students today who think their careers will suffer unless they stay in the closet, Brett remains a role model.

Brett spoke out around campus as well. Moroney found words to live by in Brett's speech to a Sproul Plaza rally against the "Briggs Initiative" on the 1978 California ballot, which would have banned gay people from teaching in public schools:

"If people tell you that your sexuality is OK as a private matter, as long as you hide it and lie in public about it, they are the ones who have the problem," Brett told the crowd. "By being honest, we are better teachers."

Brett left Berkeley in 1991 to join Haggerty on the faculty at Riverside, later moving to UCLA.

After Brett's death from cancer, Moroney says he decided to help get a fund started in his memory to support LGBT research at Berkeley, in part because he was "amazed to find out" that there wasn't already such a fund. His colleagues on the Chancellor's Advisory Committee on the LGBT Community at Cal, among them Page-Medrich, joined in the effort.

Page-Medrich and Moroney both credit Chancellor Birgeneau with encouraging support for LGBT-related research as part of his efforts to build diversity and inclusion at Berkeley. "This support from the chancellor is really important, and I'd like to express my gratitude and appreciation for it," Moroney says.

Gay physics? Why not?

Moroney says he still hears questions of the kind that Brett faced after his famous lecture: Can there be such a thing as gay musicology? His answer always was, "If there isn't, don't you think there should be?"

To people who ask Moroney if there's such a thing as LGBT scholarship in, say, nuclear physics or astronomy, he answers in the same spirit: "Why not? And if someone comes up with a ground-breaking project, shouldn't we want to support that happening at Berkeley?"

Moroney would like to see Berkeley endow a chair, as Harvard recently did, explaining: "Think of handedness: Can you imagine doing scholarship on right-handedness without including the experience of left-handers? Expanding LGBT studies increases our understanding of sexuality and gender in general and the ways they can affect all intellectual disciplines. Supporting LGBT scholarship is good for heterosexual scholarship as well."

It will be a year or so before the Brett Fund awards its first fellowships. More information about the fund is available at lavendercal.berkeley.edu; donations may be made at givetocal.berkeley.edu (search for "Brett").