|

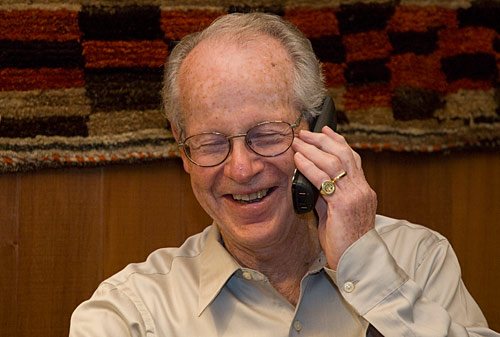

In the early morning hours Monday, new Nobel laureate Oliver Williamson receives a congratulatory phone call from a colleague. (Steve McConnell/ NewsCenter photo) |

Stockholm calling

'Long overdue' Nobel for Berkeley economist honors multidisciplinary work

| 12 October 2009

BERKELEY — When Oliver Williamson's phone rang at 3:30 Monday morning, he wasn't entirely surprised to find the Nobel Prize committee on the line.Also:

So Sunday night, Williamson alerted his son, visiting from Poland, that "it was conceivable" there would be a call the phone was in the guest room.

"And I said if there is, answer the phone," says Williamson. He did, and came to his father saying, "I think this is the call."

An elated Williamson picked up the phone and learned he had won the Nobel Prize for Economics for his groundbreaking work analyzing the economic repercussions of the ways various markets and institutions are organized. He shared the prize with Elinor Ostrom of Indiana University.

The phone never stopped ringing after that, with calls from the press and well-wishers all over the world.

"I am a lucky guy," said Williamson, latest in a string of Berkeley Nobelists. In the audience to laud his colleague was 2001 economics Nobel winner George Akerlof.

Williamson (seated) is introduced at Monday's press conference by Haas Dean Rich Lyons (right) and economics chair Gérard Roland. (Peg Skorpinski photo)

Williamson (seated) is introduced at Monday's press conference by Haas Dean Rich Lyons (right) and economics chair Gérard Roland. (Peg Skorpinski photo)The multidisciplinary nature of Williamson's work, melding social science with economic theory, was evident in the lineup of deans on hand to help introduce Williamson: Social Sciences Dean Carla Hesse, Berkeley Law Dean Christopher Edley, Economics Department chair G้rard Roland, and Haas School of Business Dean Rich Lyons. Williamson is the Edgar F. Kaiser professor emeritus of business, economics, and law at the Haas School, and a professor of economics in the College of Letters and Science.

"A couple of days ago, I was quite surprised at 5 o'clock in the morning to learn that my former student had won the Nobel Peace Prize," said Edley, referring to President Barack Obama, whom he taught at Harvard. "But this morning, I was not surprised at all to learn that Olly Williamson had won this long overdue recognition from the Nobel committee."

Williamson, he said, exemplifies the multidisciplinary approach that gives Berkeley its unique intellectual atmosphere. "It's one of the glorious things about this campus, that scholars don't live in silos but share their talents," he said.

The theme was echoed by Lyons, who called multidisciplinary work "part of Berkeley's DNA."

Roland introduced Williamson as "one of the founding fathers of new economics," saying he had "a very important role in bringing institutions to the forefront of economic theory."

The research recognized by the Nobel committee is Williamson's work looking at the ways various institutions are organized and how that affects economic activity.

Asked how his research might have tuned people into the problems that caused the current global economic crisis, Williamson said macroeconomists who look at issues like inflation, employment and the Gross National Product were better qualified to answer. But, he added, "I do think organization is important in a pervasive way," and he called for more research into organizational economics.

At a reception at the Haas School of Business, Williamson is congratulated by throngs of joyful students. (Peg Skorpinski photo)

At a reception at the Haas School of Business, Williamson is congratulated by throngs of joyful students. (Peg Skorpinski photo)Just as there's a Council of Economic Advisers to analyze economic developments and counsel the president on policy, Williamson said, "We should think about having a Council of Organizational Advisers.

"I think the issues are too important to fail to treat in a systematic way," he added.

To people looking for simple solutions to the world's economic woes, Williamson pointed out that the markets hold many benefits as well as causing some problems, and "there is no silver bullet."

"We've come a long way and we've made some mistakes some (of which) we should have avoided. That's the challenge for the future."

As for Berkeley, which along with rest of the University of California is reeling from recession-related budget cuts, Williamson said he "just cannot believe" that Sacramento "won't recognize that this is a resource (that) if once squandered, could never become reassembled.

"And therefore there's a duty, not only on our part to hang together through this, but for the state government to step up and finance the state university through these times of trouble."

In the meantime, Williamson plans to direct his own Nobel winnings he splits the $1.4 million prize with Ostrom into worthy projects. And he's looking forward to one perk that comes with a Nobel prize a campus parking place.

With that news, the audience at the press conference rose in a standing ovation.

Then Williamson was off to make the rounds of celebrations, starting in the lobby of the Haas faculty building, where the throng included Daniel McFadden, the school's last Nobelist in 1994. People sipped bottled water, sparkling cider, and some 23 bottles of California bubbly while Williamson, hard on the heels of an interview with Bloomberg TV, grabbed a bite to eat. As an electronic monitor flashed rotating pictures of the Haas "Hall of Fame," Williamson took the podium to cheers and cries of "Olly! Olly!"

Following the Alumni House press conference, Williamson shares a kiss with his wife, Dolores. (Peg Skorpinski photo)

Following the Alumni House press conference, Williamson shares a kiss with his wife, Dolores. (Peg Skorpinski photo)"It's been such a joy," he said, looking back on his decades on the Berkeley faculty. "I don't intend to quit quite yet, but I do think the torch is being passed to a new generation of scholars" who will carry on his brand of interdisciplinary economics.

"This is a great day for the university," declared Williamson. And then dozens of well-wishers pushed to the podium to shake his hand, hug him, and snap cellphone photos, all of which he happily accommodated.