|

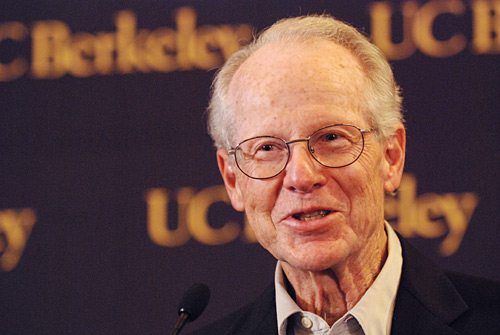

Berkeley professor Oliver Williamson answers questions from the press hours after being named a winner of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. (Peg Skorpinski photo) |

UC Berkeley's Oliver Williamson shares Nobel Prize in economics

12 October 2009 | Last updated 12:05 PM

BERKELEY — Oliver E. Williamson, the Edgar F. Kaiser Professor Emeritus of Business, Economics, and Law at the University of California, Berkeley, a pioneer in the multi-disciplinary field of transaction cost economics, and one of the world’s most cited economists, is a winner of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences.

Williamson shares the prize with Elinor Ostrom, Arthur F. Bentley professor of political science and professor of public and environmental affairs at Indiana University. Both were recognized for their analyses of economic governance.

Announcing the award from Sweden today (Monday, Oct. 12), the Economic Sciences Prize Committee of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences cited Williamson, 77, "for developing a theory in which business firms serve as structures for conflict resolution."

Williamson, the prize committee noted, focuses on the problem of regulating transactions that are not covered by detailed contracts or legal rules. He has argued that markets and firms should be seen as alternative governance structures that differ in how they resolve conflicts of interest.

UC Berkeley Chancellor Robert J. Birgeneau said, "We congratulate Oliver on this well-deserved honor for his groundbreaking work in economics. He takes his place as the fifth Berkeley economics professor to win the Nobel Prize and further continues the remarkable contributions UC Berkeley has made to this field.

"We are so pleased to count 21 Nobel prizes altogether for our campus. This award showcases the faculty excellence that resides at UC Berkeley and the level of contribution this institution makes to the country and the world."

Williamson’s interdisciplinary interests are reflected in his joint appointments at the Haas School of Business, the Department of Economics, and the UC Berkeley School of Law, and he has described his own work as a blend of soft social science and abstract economic theory.

Williamson is credited with co-founding "New Institutional Economics," which emphasizes the importance of formal institutions, as well as informal institutions such as social norms, and how they affect transaction costs. Previous emphasis had been on market impacts on prices.

His insights have been applied to improving understanding of a broad range of organizational and institutional compacts, such as the choice and design of contracts, corporate financial structure, antitrust policy, electricity deregulation in California, investment in Eastern Europe, congressional committee structure, the function and operation of political systems, and the size and scope of firms.

Williamson’s ideas about contract theory have proven extremely influential to developments in the theory of the firm, and have become central to the fields of both business economics and industrial organization.

The transaction cost approach was proposed by British economist Ronald Coase, who received the Nobel Prize for it in 1991, but Coase later credited Williamson with turning his ideas into a testable, predictive theory.

Juggling predawn press calls and congratulations, Williamson chats with visitors at his Berkeley home. (Steve McConnell/ NewsCenter photo)

Juggling predawn press calls and congratulations, Williamson chats with visitors at his Berkeley home. (Steve McConnell/ NewsCenter photo)Williamson is the author of several books, including an economics classic "Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications" (1975), and its sequel, "The Economic Institutions of Capitalism: Firms, Markets, Relational Contracting" (1985). The latter is reported to be the most frequently cited work in social science research.

His award today was preceded by Nobels for UC Berkeley economists George Akerlof in 2001 and Daniel McFadden in 2000. The late John C. Harsanyi, who was professor emeritus at both the Haas School of Business and UC Berkeley’s Department of Economics, won the prize in 1994, and the late Gérard Debreau, an emeritus economist, was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1983.

Akerlof was among the first of Williamson's colleagues to congratulate him.

"I am ecstatic that the Nobel Committee has given this year's award to Olly Williamson," said Akerlof. "Long before the internal operation of firms was on the radar screen of almost any other economist, Olly did the seminal work in this area."

Akerlof said Williamson’s "insights into the incentive structure within firms and organizations dominate the field. His theory also describes the reasons for the boundaries of the firm. From the beginning, his theory was very modern, and it has helped shape modern economics."

"I remember reading Olly's work when I was in graduate school. I was blown away," said Richard Lyons, dean of the Haas School of Business and a faculty colleague of Williamson's. "There is great beauty in the way he integrated our thinking about markets and firms. His ideas still excite me.

"On top of his brilliance, Olly is also a genuinely warm, kind person. His students, colleagues and other friends rejoice that such an honor has come to one so deserving, in personal and in academic terms."

Lyons added that Williamson's Nobel honor was "long overdue." At the Haas School, Williamson works with the Business and Public Policy Group.

"Asset-specificity and opportunism mean that firms transacting with each other can engage in 'holdup behavior,'" said Roland. "If firm A has invested in the relation with firm B, the latter may renege on its commitments and exploit A's reduced bargaining power due to the specificity of its investment."

Williamson served as a special economic assistant to the head of the antitrust division of the U.S. Justice Department from 1966-1967 and has consulted for the National Science Foundation and the Federal Trade Commission.

He earned his undergraduate degree in management from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a master’s in business administration from Stanford University, and a Ph.D. in economics from Carnegie-Mellon University. He has received 10 honorary doctorates from universities around the world.

A native of Superior, Wis., Williamson first came to UC Berkeley as an assistant professor in economics in 1963. He left in 1965 to teach at the University of Pennsylvania and Yale University, but returned to UC Berkeley in 1988.

He is a member of the National Academy of Sciences and a fellow of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and a fellow of the Econometrics Society. He also was the 1999-2001 president of the International Society of New Institutional Economics. At UC Berkeley, he was chair of the Academic Senate in 1995.

Williamson is the founding editor of the Journal of Law, Economics and Organization. In 1988, he received the Irwin Award for Scholarly Contributions to Management from the Academy of Management.

Williamson was honored in September as a 2007 Distinguished Fellow of the American Economic Association, which cited his influence in shaping the way economists think about firms, contracts and the economics of organizations.

In 2004, he received the H.C. Recktenwald Prize in Economics, the premiere German prize in economics, for his contributions to the development of transaction cost theory and institutional economics.

Williamson loves to fly-fish and is an amateur welded-metal sculptor. He also is known for donning elaborate academic regalia for UC Berkeley’s annual Charter Day celebration — a dark top hat with a gold seal and a shiny, three-foot sword given to him during honorary degree ceremonies at Turku University in Finland.

He and his wife, Dolores, have five children: Scott, Tamara, Karen, Oliver Jr., and Dean.