A

woman roasting peanuts in Daniela's neighborhood |

Face to face with the catalyst for this case, revisiting the Butterfly

sisters, and bewilderment as the country mourns a dictator

SANTO

DOMINGO, THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC — At

last it was time to meet Daniela. As readers of these dispatches

may recall, Daniela is the Dominican teenager expelled from school

because she had no birth certificate (see

About the Project).

MUDHA

staff members Sirana, Elba, Mariela and I piled into MUDHA's SUV.

Ruben was behind the wheel, which was a good thing because there

are no seatbelts to be found in the back and Dominicans cut, swerve

and dodge on the road with as much fervor as they do on the dance

floor — but with much less grace. The

midday sun was pounding down ferociously on Santo Domingo, and

between the stifling heat and the suffocating dust and exhaust

swirling up from the roadway, we chose the latter, and rolled

down the windows. At each intersection, roaming vendors strolled

by the windows hawking water, peanuts, gum, and cell-phone accessories.

Ruben

guided us out to the edge of the city, where the landscape opened

up, revealing the foothills that roll away into the volcanic mountain

ranges occupying the center of the island. We were in what must

be a suburb of sorts: a paved street lined with one-story, cement-block

homes on which decorative but sturdy ironwork covers all possible

points of entry.

Every

100 meters or so, we passed massive speakers blasting bachata,

salsa and merengue music at incredible volume to announce the

presence of a "colmado." In the Dominican Republic,

colmados service the basic needs of the surrounding homes with

a limited supply of household goods, canned foods, simple vegetables,

a few wheels of cheese and some meats for slicing, as well as

a truly impressive quantity and variety of liquors, from the obligatory

"Presidente" brand beer to carefully aligned rows of

whiskey, rum and mixers.

Daniela's

neighborhood

Turning

suddenly at one of a hundred dirt alleys between the cement-block

homes, Ruben took us off the main road. We shot past the suburban

fringe and entered the world of the batey beyond. The paved street

gave way to packed earth roads that cut through dwellings of wood

and scrap tin. The buildings look hastily constructed, though

they are probably the product of a laborious collection of materials

over time.

| |

|

|

Does she

wonder, like me, what difference

it will all make in the end?

|

Everyone

in the batey was engaged in avoiding the sun. A group of adolescents

concentrated on a game of dominos under the shade of a mango tree.

Two old men peered out from just inside the dark interior of a

doorway. A woman selling small bags of peanuts wandered down the

lane under cover of an enormous umbrella. A pack of the ubiquitous

mangy dogs occupied the gutter beneath a house.

Ruben

and Mariela shouted out greetings to friends, and a few folks

emerged briefly to exchange a few words. Clothes were hung out

to dry around almost every home, draped over power lines, bushes,

barbed wire, doorways. The prodigious collection of plastic tubs

and buckets lying about testified to the residents' ongoing struggle

to keep a sufficient supply of water on hand.

This

is Daniela's neighborhood.

Ruben

parked the vehicle under a tree, and we followed a trail winding

between dwellings until we arrived at the house of Daniela's family.

They came out, greeted us warmly and ushered us into a shady patch

in the yard with a few chairs. As we sat down, Sirana took charge

of introductions. The cast of characters that had existed for

me primarily in the pages of legal briefs and memos now took shape.

Across from me was Yolanda, Daniela's older sister; to my right,

Miranda, Daniela's mother. (As usual, I am changing the names.)

I

didn't need any introduction to the young woman on my left. At

16, Daniela is tall, slender and beautiful. She has a serious

look that broke into a shy smile when I shook her hand.

| |

|

|

"It scared me to think that

they might pick me up and take me away. That's happened

to several people around here."

|

I

was tempted to ask her a thousand questions: what does she make

of all of this? Is she aware that her case could set new precedents

in international law for this hemisphere? Does she imagine the

law students and lawyers, in offices and universities in Santo

Domingo, Costa Rica, California, New York and Washington, D.C.,

who have spent late nights over the past five years nurturing

her story into a legal argument? Does she wonder, like me, what

difference it will all make in the end? Is it worth it to her?

But

I reminded myself that Daniela has never seen me before. Better

to start off with something simple. So I asked her how the school

year went.

"Fine,"

she replied.

Protests

erupted from the other members of Daniela's family: "She

was one of the top students this year! And last year, she was

the head of her class. She's a very good student."

Daniela

smiled down at her lap. I could tell she was both a little proud

and a little embarrassed by her family's acclaim.

I

asked them to tell me the whole story.

Barred

from school

Daniela

was born and grew up near Sabana Grande de Boya, close to the

center of the Dominican Republic. Miranda, her mother, is Dominican.

Her father, who no longer lives with the family, is Haitian. Though

she did not have the required birth certificate, the teachers

at the local school allowed her to attend anyway. Then, in 1997,

Daniela's family moved to their present home near the capital.

This time, when Daniela went to enroll in the local school, the

administrators said no. Without a Dominican birth certificate,

they could not permit her in the classroom. Daniela's family was

distraught. They went to MUDHA for assistance, and MUDHA helped

them prepare the papers for a late birth registration. But the

civil registry rejected the petition. She's Haitian, the officer

declared, and there was nowhere to appeal the decision.

|

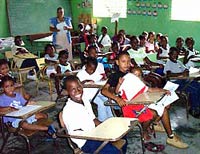

| Twelve

of these schoolchildren don't have birth certificates.

Unless things change, they will be prevented from continuing

beyond eighth grade. |

To

keep up her studies, Daniela enrolled in a night school for adults.

Daniela hated night school. She had to walk home in the dark.

Fights broke out frequently. One night, one of the students was

stabbed.

A

year later, on the orders of the Inter-American Commission on

Human Rights, school officials permitted Daniela back in the classroom.

But Daniela was still afraid.

"It

scared me to think that they might pick me up and take me away,"

she said, referring to the fact that, without papers, she could

be deported to Haiti at any time. "That's happened to several

people around here." The shy smile had now faded from Daniela's

face.

"She

had a lot of trouble sleeping back then," Yolanda added.

"There were rumors going around about her. She was really

afraid. When they were learning in school about the Mirabal sisters,

she started to think that maybe the same thing would happen to

her."

The

discussion went on. I updated them on the status of the case and

gave Daniela the diary that Hillary Ronen, the Berkeley law student

who worked on the case last year, had sent. We took some photos.

By the time we began to say goodbye, the mood had lightened and

Daniela's smile had returned.

Butterfly

dreams

But

Yolanda's comment about the Mirabal sisters stuck with me. When

I got home that evening, I searched Raquel's bookshelf, pulled

down a copy of "In the Time of the Butterflies," Julia

Alvarez's book chronicling the lives of the Mirabal Sisters, and

began reading fervently.

Minerva,

Patria and Maria Teresa Mirabal were key leaders in the clandestine

movement to topple Rafael Trujillo, the dictator who kept the

Dominican Republic under his brutal command for 30 years until

his assassination in 1961. Code-named the Butterflies, the sisters

became heroes of the anti-Trujillo resistance. In an attempt to

bring them under control, Trujillo imprisoned the women for months

and tortured their husbands.

But

under international pressure, the dictator finally released the

sisters. Two months later, they were ambushed on the road to visit

their husbands (who were still in prison). After smashing the

sisters' heads repeatedly until they were dead, Trujillo's henchmen

hauled the vehicle into a ditch to make it appear as if there

had been a terrible auto accident. No one was fooled.

Let

it be...

I

think back on the conversation we had that afternoon in Daniela's

family's yard. When Yolanda mentioned the Mirabal sisters, Sirana

had been quick to intervene.

"Trujillo

is dead," she said, but there followed a silence that indicated

that neither Sirana nor anyone else present thought that settled

the issue.

| |

|

|

Ask the Author:

Tim

Griffiths has agreed to answer your questions, time permitting.

Email

Tim in Santo Domingo.

|

I

have been thinking about this a lot over the last three days.

Early Sunday morning, former Dominican president Joaquin Balaguer

died at age 96. It is no secret to anyone that Dr. Balaguer, as

he was known, was intimately involved in the later years of the

Trujillo dictatorship. He may very well have been in on the plot

to kill the Mirabal sisters. Nor does anyone seriously deny that

Dr. Balaguer presided over the disappearance, torture and murder

of his political enemies during at least his first term in office

as president. Nor, finally, does anyone really pretend that Balaguer

was not the author of the 1994 presidential election fraud that

brought him briefly back to power.

And

yet the government, controlled by a huge margin by a party supposedly

opposed to Balaguer, has declared three official days of mourning,

during which politicians, priests, journalists and the president

have fallen all over themselves to eulogize this man. The outpouring

of devotion has taken up nearly every page of the newspapers and

hour after hour of television programming. All without a single

word of criticism or mention of controversy.

Trujillo

is dead. But the mental servility that he demanded of the

Dominican people casts a long shadow into the present. It

is still better to let things be; still best not to pursue

justice too loudly nor truth too vigorously; still wisest

to praise the powerful and scorn the gadfly.

For

Daniela and her family, I now realize, the real struggle is —

as much as anything — against that legacy.

—Tim

Griffiths

|