![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

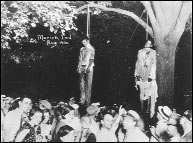

Disturbing Photo

Collection Provides Snapshots Into Past

By Janet Gilmore,

Public Affairs

Posted April 12, 2000

|

|

|

In photo after photo, the limp bodies of black men and women dangled from trees and posts while a crowd of white men, dressed in slacks and crisp white shirts, posed for the camera along with their families.

"You had to ask yourself, who'd want to go out and buy a book like that?" said Litwack, a history professor and expert in black history.

As it turns out, plenty.

The book, written by an Atlanta collector named James Allen, has sold 10,000 copies since its release in mid-February. And hundreds of people this winter braved the New York cold to view a traveling exhibit of the photos used in this new book, "Without Sanctuary, Lynching Photography in America."

And the book and exhibit have captured the attention of the national news media including the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, PBS's News Hour and virtually all other major network television stations.

"No one involved with the book anticipated the reaction," said Litwack. "I didn't anticipate the reaction that came out of the black community, which flocked to see the exhibit. It's been for many people a traumatic kind of awakening."

The book includes a lengthy essay by Litwack. And Allen continues to rely on the scholar to provide the press and public with historical insight into the photos.

Litwack wrote the 1980 Pulitzer Prize-winning book on slavery, "Been in the Storm So Long." His most recent book, "Trouble in Mind, Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow," closely examined the era now depicted in "Without Sanctuary."

Between 1882 and 1968, an estimated 4,724 blacks were killed by lynch mobs, according to Litwack. The mobs were made up of town leaders and ordinary citizens who wanted to keep post-slavery blacks in their place and uphold the supremacy of the white race, Litwack contends.

Allen, who has made his living collecting and selling old artifacts and furnishings from the South, acquired his first lynching photograph some 15 years ago. He bought the photo because it was odd, unusual. But over the years, as he has collected scores of such photos, he has come to view the images as a revealing, unblinking look into our country's past.

Litwack initially wrestled with whether the photos should be collected in book form. Would they be used for voyeuristic purposes? Would they reinforce an image of blacks as victims? Would the images be far too painful to view?

He now believes the timing was right.

"It is a time of racial backlash and retreat, and these photos point out how important it is that we not lose sight of what happened in the past and how ordinary, God-fearing citizens carried out these extraordinary atrocities," Litwack said, "that we understand that the consequences are still with us -- particularly in our racial attitudes today. You can look at these photos and think about the Diallo case in New York."

![]()

![]()

April 12-18, 2000

(Volume 28, Number 28)

Copyright 2000, The Regents of the University of

California.

Produced and maintained by the Office

of Public Affairs

at UC

Berkeley.

Comments? E-mail berkeleyan@pa.urel.berkeley.edu.