Berkeleyan

Listening for the not-so-faint echo of the '60s

For two Berkeley researchers, communes and their denizens offer a fertile field for scholarship

![]()

| 03 May 2006

Tie-dye is in style again and Summer of Love memorabilia can fetch stiff prices at auction. Yet the era known as "the '60s" remains poorly understood and fiercely debated - as two Berkeley scholars discovered recently when they set out to learn about communitarian experiments of that time.

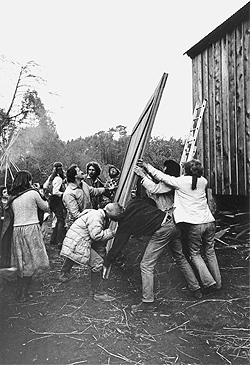

Northern California communards, in 1974, prepare to set in place the door - constructed of wood salvaged from a building on the Berkeley campus - for their community house. (Photo © Ilka Hartmann 2006) |

No need to venture far, they thought. California spawned scores of communal experiments in the '60s, some of which must have been written about by scholars, figured Watts: "We assumed that the commune, whether rusticated or urban, was a well-plowed field."

They were wrong. True, the United States has a long, well-documented tradition of communitarian living projects - the Amana Society, the Hutterites, the Oneida Community, and the Shakers being but a few examples. And during the 1960s, tens of thousands of young people simultaneously joined that stream, founding rural and urban communes, mostly secular in nature.

Utopias west of Eden

Yet Watts and Boal discovered that a history of the '60s commune movement "has barely been approached..It must be connected to the general anathematizing of the '60s, not least the tacit sneer whenever the word 'commune' is pronounced," Boal said in opening remarks for "West of Eden: Communes and Utopia in Northern California," a conference at Berkeley in March.

There, scholars, students, and former communards explored such topics as the San Francisco Diggers (a group, launched in 1966, that combined street-theater art happenings with a vision of a "free city"), the Black Panther Party and its school-breakfast program, Project Artaud (an artists' live-work space in the north Mission, founded in 1971), FBI surveillance of Black Bear Ranch (a radical commune in Siskiyou County), the '60s-era Whole Earth Catalog (which called itself an "operating manual for spaceship Earth"), sexual and class politics of the commune movement, and '60s architectural innovations (including, most famously, the geodesic dome).

| "Smashing down the wall" Student Conduct Officer and former communard Hal Reynolds recalls his days on "McGee's Farm." |

Actor Peter Coyote, co-founder of the Diggers, was quoted as saying: "While we developed refined vocabularies to discuss free economies, bioregional borders, inter-commune trade, media manipulation, political subversion, and drug-related mental states, we possessed almost no tools for discussing interpersonal conflicts and personal problems or resolving the sometimes catastrophic or claustrophobic stresses and strains of communal existence."

Is the commune movement, therefore, to be viewed as a historical failure? participants asked. Or is it the case, as Boal suggested, that "legacies of communalism in all its forms now permeate the wider culture"? As evidence of the latter possibility, he cited "foodways" such as the organic-food movement and the now universal practice of unit pricing in grocery stories (introduced by Finns from Fort Bragg who founded the Berkeley Coop in the 1930s and invented "this obviously rational thing"), protocols for meetings and decision-making, changes in gender politics and childrearing mores, and a "very widespread green sensibility." The same might be said of natural birthing and the barter economy.

"The echo of the commune, if you listen for it," Boal asserted, "can be heard virtually everywhere in contemporary California, and beyond."

A 'ferocious' reception

"West of Eden" was the second conference under the umbrella of the Communes Project, which has also entailed a 2004 conference on communes of Mendocino County, an undergraduate course on "Experiments in Community," and discussions with former communards concerning the possibility of (naturally) a collective project.

The latter, facilitated by historian Cal Winslow, director of the Mendocino Institute, "was one of the most extraordinary projects I've undertaken as a scholar," recalls Watts - whose past fieldwork has taken him to west Africa, south Asia, and Vietnam to study peasant agriculture, Islamic social movements, and the political ecology of oil.

This time, Watts traveled with Boal to Albion Ridge, on the Mendocino coast north of Elk, to meet with "men and women, (mostly, like Iain and myself, '60s people') who had been in communes," Watts recalls. The two scholars' initial reception, he says, was "skeptical and occasionally quite hostile." Former communards peppered them with angry questions: "'Why are you here?' What was our interest? Were they to be involved? 'Are you going to take our story and make money on it?'"

Watts and Boal explained that they saw the commune movement as an important and untold story of the New Left in America. Gradually, Watts recalls, "people began to open up, anxious to tell their own stories of success and failure, and to reclaim their history from what the great historian Edward Thompson called 'the condescension of posterity'; it was extraordinarily moving."

The ferocious response, former communards told them, was because "many of us feel we failed. You're asking us to relive a history of failure." At the same time, the commune experience had been formative, creating lifelong connections and ways of being for many in the room. "I'm closer to all of these people than anyone in the world," some said. After a bumpy, emotional start it became clear, Watts says, that some participants, now in their 50s and 60s, keenly wanted "to tell, from their vantage point, about building another type of life."

Watts and Boal include accounts by former communards in an anthology near completion titled West of Eden, made up of articles both from scholars and non-scholars. This work, they hope, will begin to provide a serious assessment of the commune movement, whose long neglect "is wrapped up in the effort to denigrate it," Watts reiterates.

If the varied communitarian influences of the '60s counterculture have something in common, he says, "it is surely about the construction and defense of all forms of 'commons,' holding the market at arm's length in a profound and important way." The neoconservative project, says Watts (and here lies the importance of this research for him and Boal) is to enclose the commons, privatizing what is public, from Social Security to airwaves and national parks. The hidden histories of the communes on Albion Ridge and elsewhere, he argues, have much to say to the current moment, "when the very idea of the public and collective is being put to the test of the market."