Berkeleyan

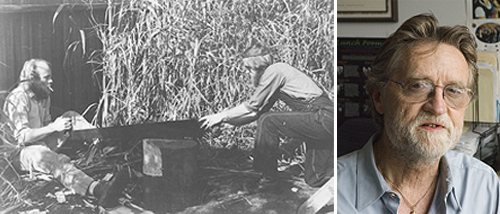

At left, in the spirit of communal work, Hal Reynolds (pictured right) and fellow men's-group member John King build a children's play structure, circa 1970. At right, Reynolds today. |

Student-conduct officer - a former communard - recalls 'smashing down the wall'

![]()

| 03 May 2006

| Listening for the not-so-faint echo of the '60s For two Berkeley researchers, communes and their denizens offer a fertile field for scholarship |

A casual call, via campus e-mail, for former '60s communards in our midst - there must be dozens - quickly yielded Student Conduct Officer Hal Reynolds, who took part in that generational experiment just blocks from his current Sproul Hall office. In 1969, Reynolds and his wife, Turi, bought a four-bedroom house (for $16,000) near McGee Avenue and Channing Way, and invited others to join them in forming an urban commune. Two young followers of New Age avatar Meher Baba were the first to join, followed later by a priest and nun who had recently left the Catholic Church - and a changing roster of others.

Unlike many '60s communards, Reynolds didn't approach communal living from a "deeply ingrained left-wing ideology," he says. "Part of it was very practical. We wanted to get help with childcare." The political culture of the day, however, envisioned more radical projects, as in a political poster that Reynolds remembers vividly: "It showed a house with people jammed inside it looking very stressed; it was titled 'Smash the Nuclear Family.'"

Members of Reynolds' commune, dubbed "McGee's Farm," shared housework, childcare, cooking and meals, political activism, and "constant meetings," and contemplated sharing a car and the deed to the property. The house had previously been two flats with a wall between them. "One of the great communal things we did was smash down the wall," he says - though they never attempted, as in some communes, to deconstruct individualism, private property, or patriarchy by completely merging their finances or sharing sexual partners.

Reynolds was a student at Berkeley at the time, studying for his doctorate in comparative literature; he and his wife had two young children and were older than many local communards. "We were on the responsible track; we weren't dropouts by any means, but we were swimming in the same water."

Neighborly feeling ran high. Many in central Berkeley were immersed in the counterculture; "red-diaper babies" founded several local communes, including one around the corner called "Karl Marx's Magic Bus," he recalls. "Our neighborhood had a cohesiveness we all miss - men's groups, women's groups, childcare, a lot of cooperation and collaboration. On the other side," he says, "there was a huge idealism and naiveté about what it takes for people to live together and get along."

Reynolds helped form what he believes was one of the first local men's groups - whose members provided childcare for the neighborhood "in the strong belief that taking care of children was not just the responsibility of parents, and especially not of just the mother." Male bonding also produced more "manly" skills (Reynolds remembers vividly the dose of self-confidence he gained by learning to fell a giant tree with a chainsaw) as well as more conventional political ones, like staging a lively protest. His men's group once showed up at the Playboy Club in San Francisco - in the late afternoon, "when men were coming out of their office buildings" - with an anti-sexism skit and loaves of homemade bread. "This was an alternative to the beautiful babes inside, that they would want our bread instead?!...We were going to change the world."

He also belonged to an affinity group that held anti-war protests at Lawrence Livermore Lab and added a kayak contingent to a "peace Navy" flotilla protesting Fleet Week.

Reynolds looks back on McGee's Farm and associated projects "with a certain mixture of embarrassment and yet pride. That insight we had, about men being responsible for childcare, was absolutely right on," he thinks. Though the commune lasted only a few years, and ambitions like smashing capitalism and the nuclear family did not pan out, "little things that we worked on," such as the organic-food movement, "eventually crept into the mainstream in a lot of ways."

After 29 years at Berkeley - four as a graduate student, three as an instructor in remedial writing, 20 as a student-affairs officer, and the last two in his present job - Reynolds, now 67, is planning to retire at the end of June; he plans to return later this year, on a part-time basis, to continue working with students charged with violating the campus Code of Student Conduct, sometimes as a result of their protest activities. (For a decade he also directed the Campus Observer Program, which provides neutral observers at student political actions.)

"Defying the prevailing paradigms gives you a lot of energy to connect with people," Reynolds says. "It's ironic that a big part of my work here turned out to be about protests."