Berkeleyan

|

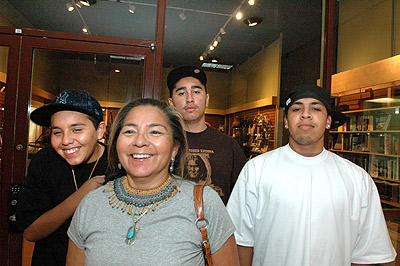

Luisa Armijo brought Native students to Berkeley, because it's the campus she knows best: Two of her four children have attended Cal, and a third started this fall. (Peg Skorpinski photo) |

Teaching tribal teens the write stuff

Luisa Armijo created a writing-immersion program to help Native youth feel at home on the page - and fuel their dreams of college life

![]()

| 04 October 2006

Traveling to Berkeley from Thermal in Riverside County, the desert community near the Salton Sea where the Torres-Martinez Desert Cahuilla Indians make their home, takes about 10 hours by car. For most people, that distance is easily traversed - a day or two's drive or a short plane flight - but for many of the tribe's high-school students, the trip is a journey to another world.

To bridge that distance, tribal education and library director Luisa Armijo developed and piloted a writing-immersion program this past summer to help eight Native teenagers improve their skills and get a leg up on their college applications.

American Indian students face any number of obstacles to getting into a four-year college, says Armijo, two of whose children have attended Berkeley, with a third starting this fall. In addition to lack of college preparedness and adequate counseling, many of the students have not developed writing skills, though most are practiced at storytelling, the heart of Native American culture.

The statistics on the number of American Indians enrolled at Berkeley underscore the problem. Since 1998, the number of American Indian freshmen has never crept above 22 new students, representing at best 0.6 percent of each incoming class.

On a writing journey

Youth from the Torres-Martinez reservation are culturally identified with their heritage - they practice traditions such as birdsinging and bird dancing, and take classes in Cahuilla, their native tongue. The Native youth "have a lot of traditional experiences they don't get to express in school," says Armijo, who in devising the writing program wanted to address the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, which mandates standards of accountability on schools and leaves teachers limited time to do anything but teach to test.

With the new program, Armijo's goal is "to help the students express their stories through a writing journey." To that end she made two trips to Berkeley by car this past summer, bringing four girls to visit the campus in mid-July, then returning with four boys the following week.

Each group took a campus tour, then delved deeper into Berkeley with visits to the Campanile, local publishers Heyday Books and Ojate (both publish works by Native Americans), and the Hearst Museum of Anthropology, where students saw baskets woven by their ancestors and learned about Native American repatriation efforts (On the latter topic see www.berkeley.edu/news/berkeleyan/2005/11/03_repatriation.shtml.)

The teens met admissions representatives and Native American Cal students, toured the Native American Studies Collection, and took in local sights. After each activity the students tackled a writing lesson designed to encourage free expression.

"They don't do enough of that in schools," charges Armijo. "Many of them are in classes where they have to write to task." The students had never received permission to write without worrying about errors, so they felt inhibited. "Their hidden passion and self-expression needed to be explored and encouraged," Armijo explains.

Throughout the program, the two teachers Armijo enlisted provided assignments to the students, interacted individually with them, and gave feedback on the youths' writing every step of the way.

Such an assignment followed a visit to the UC Botanical Garden's Mather Grove: If the redwood trees could speak to you, what would they say? One student wrote as if the trees were elders; another gave the trees names, while a third imagined them in conversation with one another. "There was no classroom and no boundaries - just the students and their paper," says Armijo.

The writing prompts were intended to get students thinking about tacling the personal statement on the UC application. "These students need to know that UC Berkeley needs to know who they are," says Armijo. "Everyone they met at Berkeley brought that home to them: 'You are important; we want to know what makes you tick.'"

Helping them take another look

John Berry, a Native American studies librarian in the Ethnic Studies Library, showed the visiting youth that if they are admitted to Berkeley, there are rich resources awaiting them. "We're one of the few UC campuses that actually has part of a library specifically devoted to Native studies," says Berry; yet, he adds, it's difficult to attract Native American students. "Luisa believes Cal is the best and there's no reason our kids can't be here, so she's willing to help them take a second look at their options. I think that's just a wonderful thing."

Bridget Wilson, the campus's Native American outreach coordinator, agrees. Campus representatives travel to communities across the state to reach out to Native American tribes, but Armijo's program gives youth a chance to see the campus, says Wilson. "We can go into Native communities and say, 'You need education, you need college.' They have to respond by telling us what they need." In Armijo's case, she feels her tribe's youth need stronger writing skills if they want to attend college, says Wilson.

Wilson sees myriad challenges for Native American students at Berkeley, including few Native American faculty and little programmatic support. Many of the students come from low-income, single-parent households in which they are the first to attend college. And they often feel cut off from their home, traditions, and ceremonies when they come to Berkeley. In spite of those hurdles, Wilson is guardedly optimistic.

"If we can partner with communities," she says, "that's a really good direction, but the university can only do so much. The communities have to buy in as well and meet us halfway."